[openrouter]Summarize this content to 2000 words

892

/

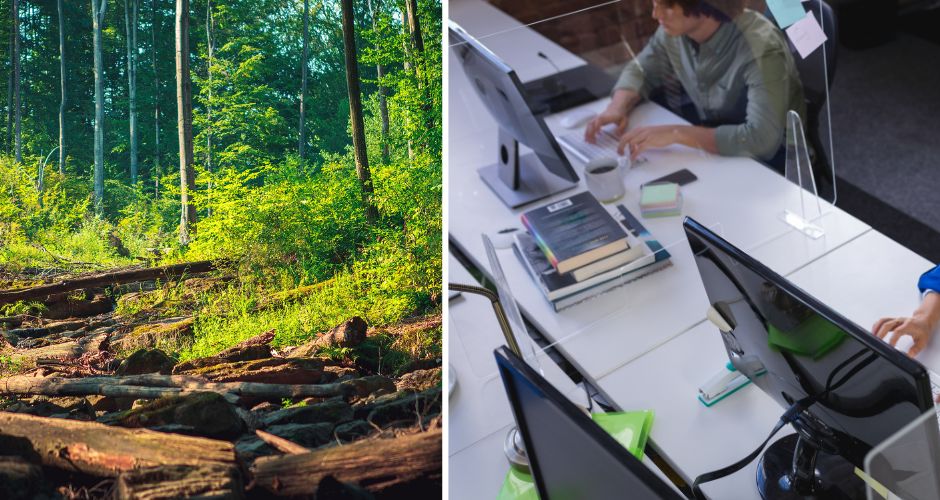

It all comes back to capitalism. In the first half of the show, economist, author, and show host Dr. Richard Wolff joins us to talk about empowerment beyond the strike, and how we can manifest true democracy in the workplace. He gives us a grotesque look inside the board room, the unfair imbalance between unions and corporations and how this affects us all, from stagnant wages to imposed inflation. In the second half of the show, Mickey Huff talks with co-host Eleanor Goldfield about her new film, To The Trees, which highlights forest defense tactics in Northern California while calling into question our current relationships to nature, how we might reframe them, and why that’s vital to our survival and a livable future.

Notes:

Richard Wolff is Professor of Economics, Emeritus, at the University of Massachusetts. He co-founded the academic journal Rethinking Marxism, and he hosts a weekly radio program, Economic Update. His website can be found here. For further information on Eleanor Goldfield’s new forest documentary, visit To The Trees Film.

Support our work over at Patreon.com/ProjectCensored

Eleanor Goldfield: Thanks, everyone, for joining us at the Project Censored radio show. We’re very glad right now to be joined once again on the show by Professor Richard Wolff, who is a professor emeritus of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

He’s currently a visiting professor at the New School University in New York. He’s also the co founder of Democracy at Work. info and its weekly radio and TV show Economic Update. Thank you. You can find more of his work at democracyatwork.info and rdwolff with two f’s dot com.

Dr. Wolff, thank you so much for joining us.

Dr. Richard Wolff: I’m very, very glad to be here, Eleanor. I really enjoy speaking with you.

Eleanor Goldfield: Likewise, thank you. So I wanted to ask you about the economics of this corporate hack of quote unquote tiered workers. This is something that we see cropping up all over the place. UPS workers were demanding an end to the two tiered system, they called it, that included a massive wage differential between full time and part time workers and between drivers and inside workers.

A recent post by A More Perfect Union outlines the way that temp workers at Jeep make half the rate of full time employees, though they do the same jobs, with some workers having been temp for more than five years with no clear path to becoming full employees.

So I wanted to start us off by asking you to talk a bit more about this trend, what it means for the corporations and what it thereby means for the workers.

Dr. Richard Wolff: Okay, I’m glad to do that. Let me just add that one of the key issues in the strike right now between the United Auto Workers and Ford GM and Stellantis is precisely the two tier system that was put in place a few years ago and is violently objected to by the workers.

Let me approach this historically, which will set the tone for it.

Karl Marx once wrote that the history of the world is the history of class struggle, whether it’s master and slave, lord and serf, employer, employee, it’s always the same. And what he meant was if you organize workplaces, like factories, or offices, or stores, if you organize them with a small number of people at the top, the major shareholders, the board of directors, the owner operator, and then below them a mass of employees, you’re going to have endless tension.

Because what the employer wants is the maximum profit out of those employees. What the employees want is a decent income to raise their families, to live their lives, to have what is nowadays called a decent work life balance, et cetera, et cetera.

And these are conflicting goals. The employer gets more profit the more he squeezes the workers. And the worker who’s fighting for better lives for themselves find themselves opposed by the employer who doesn’t want to give them that. This is a, a struggle without end.

And now we have the context. Two tiers is a way of engaging in that struggle and should not be misunderstood for being anything else. Here’s what it means.

The employers have figured out that they have a better chance of squeezing their workers to get more profit out of them by setting them against each other, by finding ways to provoke or to worsen, if they’re already there, arguments, disagreements, suspicions, all of it.

And we, we see it everywhere. Male against female. Older worker, younger worker, white worker, worker of color, and I could go on and on. But they’re creative. They don’t just deal with the old inherited conflicts like those I just mentioned. They’ve decided to add a few of their own, and one of them is the tiered worker system. Here’s how it works.

Workers now, working right now at this moment, whenever that moment is, are told by the employer, we don’t want to make life difficult for you. We will continue to pay you the wages that we’ve been paying you. No problem. All we ask is that you allow us to hire new workers when you die, when you take a different job, when you retire, whatever.

When we replace you, we want to have the right to bring in the young worker, the new worker, at a lower wage than we pay you. And, but of course, since we believe in democracy, we’re going to give you the vote in your union whether or not to accept doing this. Notice that no vote is given to the unknown people to be hired later.

So they, who might say, no, no, no, no, no, if I’m going to be doing the same work as somebody else, I want to get the same pay. They’re not allowed to vote by this little arrangement. Who does the voting? Only the workers that are there now, because they are the ones in the union who get to vote. Now, they may have a feeling that they don’t want to do to the younger generation what was not done to them by the generation before them.

Two tier is a relatively new gambit. So, a lot of those workers won’t go for that because they understand what I just said. But a bunch of others who don’t know their history, no one has taken them aside to teach them, no one is there doing it now. If you have a corrupt union leadership, it kind of goes along with all of this.

And at least immediately, the older workers won’t notice it because they’re continuing to get paid. So they are able, sometimes, to get one by on the employees who actually vote to accept the contract with two tiers.

As the United Auto Workers shows, once they understand and see it, once the older workers recognize the lesson, if you want those younger workers to go out on strike when it’s important for you, then you’re not going to get the kind of support you want if you have taught those workers not to trust you because you went along with a deal that gives them half the pay you get for doing the exact same work. And the same applies to temp workers, which is just another way of doing the same thing.

I like to talk about it not only to teach people not to be fooled, but because it’s a lesson. That the class struggle that our mainstream media avoid referring to on pain of near death, they’ll say all those seven words that Carlin told us never to say, they’ll punish that, they’ll deal with all, but to say class struggle, well that, that’s much worse than any of those seven words, which I know not to say.

The hypocrisy is grotesque here, but that’s what we’re looking at. We’re looking at Class struggle. In our moment of history.

And I think you’re seeing the United Auto Workers saying, no, fool us once maybe, you’re not gonna fool us twice. We’re not going to do this. We’re going to fight against that. And I noticed there are a number of other unions that are beginning to really push back. They’re learning that this is not only good for the employer, it’s bad for the union and all the solidarity that they would want. So they lose twice from this deal.

Eleanor Goldfield: Right. An injury to one is an injury to all. And since you mentioned the UAW, I’m curious what your thoughts are because there’s been a lot of back and forth with people arguing about the tactic of this partial strike.

And I’m curious, what are your thoughts on the partial strike as a tactic?

Dr. Richard Wolff: Well, I shy away from too much commentary on these tactics, and not because it isn’t an important topic, it’s just we can’t know.

The way these things are done, there’s a small room in some hotel somewhere where the representatives of the auto companies are sitting across the table from the union leaders of the union negotiating team, and probably in the room, either physically or spiritually, is a President Biden, and people should be very clear, he’s there because he’s worried about his election next year, as he should be, and he figures out he’s going to be in trouble, depending on how this strike goes.

So for example, and I’m not saying this is what happened because I don’t know, I wasn’t in that room and nobody who was in that room has spoken to me. So this is purely my guesswork. But here’s my guesswork that the union probably understood that its best leverage would be to take all 150,000 workers out at the same time, which is at midnight last Thursday. Okay.

Mr. Biden would have preferred a settlement, the way the Teamsters settled with the United Parcel Service a few weeks earlier. They compromised. What Biden got was, there will be a strike, you know, we’re not going to call the strike off. But what Mr. Biden got was this approach of, we’ll start with three or four plants, and if we don’t get a response from the employer, then we will broaden it out. That’s the kind of thing that often happens, because you really have all three.

The minute the union gets large, then the politicians, if it’s not the president, well, then it’s the senator or the governor, depending on the size and the number of voters affected and the publicity the thing gets. But that’s the way our society kind of works.

And the union may also have had other reasons. It’s very hard. People have to understand. It’s very hard to take workers out on strike. Remember the unfairness of it.

I’ll take just General Motors, for example. Their CEO, Mary Barra, you know, was revealed during the last two weeks to have a salary currently of $29 million a year. A salary that went up, on average, went up about 40 percent over the last four or five years. So, I mean, these people are rolling in money. Just rolling, number one.

Number two: the strike does not affect their income. They continue to be paid if the strike lasts two days, two weeks, two months, don’t make any difference.

Think how utterly different the other side of the table is. These are workers who are on strike because they’re not getting paid enough. Faced with the inflation, faced with the rising interest rates on the credit cards they all carry, etc., etc., etc., they are people that are being squeezed. And now, for every hour they’re out on strike, they lose money, because the strike pay from the union is significantly less than their pay.

So, they are taking it on the chin every day. And if you’re the union leader, even if you’re relatively militant sounding, as Shawn Fain, the new head just elected of the union is, you don’t want to take your people out and subject them to that. So you have to worry that a lot of workers are going to feel, rightly or wrongly, that you should have tried at least with a few factories at the beginning so that the others wouldn’t have to suffer if that would be enough.

So he’s going to wait a week, give the company a chance. That may be more acceptable to his members. All of those kinds of considerations are there.

But I want to stress the basic point. Labor management negotiations of this kind are really negotiations between David and Goliath.

And David is the worker and Goliath is the employer. And the question is whether the strike is a slingshot or not.

Eleanor Goldfield: A very good metaphor. And I’m also curious about that because you mentioned the Teamsters working to figure out this contract with UPS and a lot of people, particularly obviously on the left said, well, that wasn’t good enough. There was so much about the their demands that weren’t met. The rail workers ended up not going on strike thanks to, as you mentioned, Biden, basically saying that it would be illegal to do so.

And I’m curious about the class structure that also exists inside unions, you know, a lot of people were then pointing at the heads of the union saying, well, you didn’t push hard enough, you didn’t demand hard enough.

What is your perspective on that, understanding just as you said as well, that it’s a difficult thing to decide because pulling people on strike is also very damaging.

Dr. Richard Wolff: Yeah, I mean, union leaders are in a tough position. Are there some who are corrupted and basically serve as organizers of the workforce for the employer? The answer is yes, there are such union leaders, and therefore every union member in any union is always worried whether he or she admits it or not: are my leaders that way? And I hope not. That’s why there are hotly contested races, as there were in the UAW. And Shawn Fain, the new leader, who won by very little. We’re talking 100-150,000 votes. He won by 400 and some votes. So this was a, he’s got to show that he really is the better one, because an awful lot of people in that union are going to be skeptical, the ones that voted for the other side, which was more the traditional leadership.

On the other hand, you know, we subject unions to things we do not subject managers to. Unions have to show that they have democratic elections in which each union member has a vote. An equal vote. One union member, one vote. The people who elect the board of directors of General Motors don’t have that democracy. They are not elected by anyone, other than the shareholders, number one.

Everybody else, even, you know, the citizens of Detroit are deeply affected by whatever happens here. Those who work at the auto plants, but the many hundred thousand who don’t. What say do they have? They have to live with the results of this outcome, but they have no vote at it at all.

But even worse is once you look at the vote, it turns out that the shareholders have a vote per share that they own, not a vote per person. Which means, to give you an example, that any of the large major banks in this country, Citibank, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, Chase, JP Morgan bank, they are the trustees for large blocks of stock that are owned by wealthy corporations, wealthy individuals. So they come into the annual meeting with, get ready now, hundreds of millions of votes. One banker, Banker John or Banker Mary, comes in there and votes a million times.

Your grandmother, who might have gotten a gift at some point in her life of ten shares of General Motors, she gets ten votes. But she doesn’t bother knowing about it, or going to the meeting, because she knows her votes mean nothing.

If you talk to grandma, and this is not because grandma isn’t smart, or grandma isn’t educated about these things. Grandma, if she’s smart and educated, knows that spending her money to go to the meeting of, the annual shareholders meeting is an utter and complete waste of her time because her votes are completely overwhelmed.

A tiny group of people, and let me stress this, often it’s 30 to, I’ve been to meetings of annual shareholders, 30 or 40 people are in the room and the outstanding shares: 50 million. So those 30 people are voting the shares of the 50 million. It’s disgusting.

So you have the union, which has to, is supervised by the government, National Labor Relations Board. It must adhere to democratic rules in which one person has one vote and you can’t mess around with that, in the union election. On the other hand, you have a very cozy system of 30, 40, 50 people, all of whom know each other, all of whom gather in the same room at that hotel. You know, it’s like a picnic or a family reunion where they all get together. They know what they do. They do the same thing. They go through it. I sat there. On proposition number four, how many people are in favor? 30 hands go up. How many people are against? Two people who are there because there’s free drinks. You know, it’s a joke. It has nothing to do with democratic governance.

It is the way our corporations, and they do the bulk of the business, that’s the way that they work. So it really is David and Goliath. It really is a completely bizarre way. And so the corporate leadership does what they want and they’re not, I mean, you could even make an argument. I’ll go a little further.

The union is at least a large number of people. On the other side, it’s a tiny group of people. And the two of them get together to decide what happens. Unfair conversation, unequal situation, really grotesque. But then there’s the millions of people who are going to be affected by the outcome, who have no say whatsoever.

You know, it’s a little bit like explaining to people that an inflation is one of the most undemocratic phenomena one can imagine. The percentage of our population, if you allow me for a minute, Eleanor, with this.

The percentage of our population that are employers is estimated between one and three percent of our people are in the position of hiring, firing people, being an employer. The rest of us are either employees or the dependents and relatives of employees. Okay.

Who sets the prices for the goods and services we all depend on, whether the haircut we get or the hamburger we get at the store. It’s those 3% of the people.

They decide whether the price goes up, whether the price goes down or whether the price stays the same, they make that decision. The rest of us… Pay.

We’re upset these days because they’re raising the price. Did we vote for that? Of course not. Do we have any input on it? None. No employer calls the employees in to participate in deciding what the price is of the hamburger or the blouse or the haircut.

So when prices go up, I want people to understand it’s like with that negotiation between the union and the employer. The prices are being raised by a tiny group of people at the top who seem to have, in this weird system we call capitalism, have this authority to impose on the rest of us the inflation.

And when we complain about the inflation, if the system has done its job, we will blame anything or everyone other than the people who did it. So it’ll be supply chain disruptions, or it’ll be the nasty Russians invading Ukraine, or it will be the nastier Chinese doing something. But the idea of asking the question when the price goes up, who raised it? We don’t do that. We don’t do that. It’s extraordinary. The power of ideology coming home to roost.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, absolutely. It reminds me of the example of Walmart having a little collection tin so that their workers can afford food. Or, you know, the fact that many of their workers are on the SNAP program.

And how, how long would it take for someone to go down the list of things to get to, why don’t you just pay your workers more?

Dr. Richard Wolff: Yeah, not only that, I’ve heard this story, I’ve never verified it myself, but I’m sure it’s true, that in some of the Walmart stores and other stores too, there is a desk where a person hired, paid by Walmart, you know, a regular wage, and what that person knows are how to get staff, how to get food stamps of one kind or another. And the rest of the employees at Walmart or any other store are encouraged on their way in in the morning or on their way out in the evening to stop by that desk and get some help.

And of course, the logic for Walmart is then they can get away with paying these people too little because they’re using those people’s desperation to basically force the government into subsidizing the wage.

And here’s the best part. You will then see the conservatives to whom Walmart donates, denouncing the government for subsidizing, not understanding that the reason the government does it is because Walmart wants it.

You know, if you understand the way this capitalism works, all you end up doing, which is me, is shaking your head and saying, how the heck do the American people tolerate this?

Eleanor Goldfield: Absolutely. That’s a great question I ask myself a lot.

And with that I wanted to ask kind of a broader question here, because you talk about, and indeed it’s the name of your site, democracy at work, and I’m curious, do you feel that any demands that fall short of that, you know, speaking about demands with regards to strikes that might happen, any demands that fall short of a full democratization of the workplace, i.e. worker ownership, can actually address the deep needs and the root causes, i. e. capitalism, or is this just putting a Band-Aid on a gunshot wound and hoping that it’ll see us through?

Dr. Richard Wolff: Well, in the past I might have hesitated with your metaphor, but I believe it’s correct now. I, I think what we’re seeing in the UPS strike, in the UAW strike, whatever the outcome, you’re going to be leaving a sizable residue of the members of the workers, both those who voted for the contract and those who voted against it, a sizable proportion are going to feel as you just said, that whatever the settlement was, it falls far short of what we need and what we want.

And I, let me push this, that sentiment is my best hope for how we’re going to go beyond this. And let me explain.

I have been involved in the following scene. A group of workers demand an improvement in their working conditions and their wages. The employer refuses for whatever reason, the workers go on strike or threaten to go on strike, doesn’t matter, and the employer counters and says, and by the way, the auto company and executives are saying this right now, so I could use them as an example. We cannot meet your demands. Because if we could, if we met your demands, we would sooner close the business because it’s an unviable business, it’s unsustainable, and nobody will buy a Ford or a GM car if we give you the wages you demand, and, and then we’ll die. We’ll close the factory, or maybe a variation, we’ll leave and move the factory to China, or we’ll move it to Brazil, or Mexico, or Canada, it doesn’t matter.

At this point, something happens which most Americans have not yet been able to imagine, which is my job, to help you do that. The workers say to the manager, no problem. Go. We don’t need you. We don’t want you. We’re sick and tired of every two or three years having this crazy ritual where we say we need this to get by. It’s obvious we’ve had a terrible inflation. Our wages haven’t gone up. Who’s surprised that we are arriving saying, hey, we got to get more money. We can’t get our kids to college. We can’t put food on the table, etc. You go. We’ll take this place over and run it as a worker co-op.

You know, one of the advantages of worker co-ops is, they don’t have to pay dividends to anybody, because it’s their business. They don’t have to have executives like you, Mary Barra, with $29 million, we can get someone to be a supervisor here for a tiny fraction of what we’re paying you.

And you know something? If it’s our enterprise, we have a wholly different attitude towards it. When we leave at the end of the day, we make sure to turn the light off in the bathroom so it doesn’t go all night charging us electric bills, and we make sure that the faucet works and doesn’t drip, and we make sure to oil the machinery, and we make sure that, ooh, we’re going to be more productive, because we care. It’s ours.

It’s the same logic as saying, if it’s your apartment, you take better care of it than if it isn’t. Or if it’s your, you know, pet, you take better care of it than if it’s somebody else’s pet, et cetera, et cetera.

So, go already. And you know something? This is going to change labor capital relationships in this country.

Suddenly, the workers have another weapon. They don’t just have job action. They don’t just have a strike. They can say, hey, you close it, we’ll take it over. But now it gets better.

I have helped arrange for those workers, when they’re in that situation, to go to the local mayor, or the local senator, or the local governor, and say, here’s our situation: we are going to demand it. They’re going to shut the factory or, or threaten to take it. And we’re going to say, look at them. These are bad citizens. They’re closing the factory. They’re depriving all the people of work. They’re depriving the community of the taxes they pay. They are the bad guys. We, the workers, who are going to keep this business going, thereby keep the salaries being paid, the wages, keep the taxes being paid, we’re the heroes. We’re good for this community, they’re not. We want you, the politician, to help us. Give us a subsidy. Give us a tax break. Give us the things that will make this work. And if you do that, we will be big supporters of yours. And the other message?

If you don’t do it, you won’t be dog catcher around here, because we are going to make sure everyone knows you could have saved the economic situation, but you didn’t.

This, this is a game changer. This is a new politics. This is a new economics. And for the workers, it’s a moment of empowerment they never dreamed they would have. They’re now the big shots. They’re the people who are the employer and the employee. That split is no longer there.

They are their own bosses, which has been their dream ever since they were children, to be their own boss. I used to ask in my lectures at UMass, I used to ask, I sometimes taught classes of five, six hundred people, and I would have them write down, what do you hope to do in the years ahead? The overwhelming majority of young men and women wrote, I want to be my own boss. I don’t want to sit in a cubicle in some anonymous building, you know, indistinguishable from the people around me.

So we are responding to that desire of people, to the empowerment. People will not give up once they get a taste of it. And so I think the conditions are ripening for the very ideas of transition I’m talking about to become major ways of thinking for large numbers of people.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, absolutely. And basically, like you said earlier, the trick is knowing that you have those tools in your toolkit.

Dr. Richard Wolff: That’s right. You know, it’s the old lesson, the lesson that people of color have had to learn, women have had to learn in our culture. You have the power. It’s the question of whether you can figure out how, together with others, you can exercise that power. You don’t have to be a second class citizen. And in the workplace, the employees are second class citizens, and they have to learn.

Look, the anti-racism movement, the anti-sexism movement, borrowed things like the sit down strikes from labor back in the 30s. Okay, now it’s going to go the other way. The labor movement’s going to be revived by learning the lessons of the social movements, to stand up and to refuse to do this, and refuse to accept that, and to demand a different way of functioning.

Everybody used to think it was reasonable that all the executives were male. And they all had a female secretary, as if this were somehow written in the stars. And nowadays, right, we make fun of all of that. We mock it. I mean, some of us do, but at least the direction is in the right, in the right way. I don’t see any reason why employees cannot do to the employer what was done by people of color to teach white people.

And will there be a backlash? Of course. Look at the white supremacy stuff now. Look at the hostility towards women coming up all over the place, you know.

The difference people have, who have seen the film Barbie, who see it in one way or another, I find this spectacular. Two people sitting right next to each other in the same theater, watching that same movie over the same, whatever it is, hour and a half, coming out with the most diametrical notions of what they just experienced, and then laughing when they realize how differently that this film unfolded in their minds.

You know, one who went to see the Barbie that my wife and I would not buy for our daughter years ago, versus you know, versus the people who thought this movie’s about that Barbie, rather than a takedown of that whole idea. I mean, so it’s wonderful.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yes, there is no consensus reality these days, for sure.

Well, Dr. Wolff, thank you so much for taking the time to, once again, as you always do, contextualize things and explain it in a way that people like me, who are economic idiots, understand. Really appreciate it.

Dr. Richard Wolff: It’s my pleasure. You know, I became a teacher because I had one too many experiences with people who said they were a teacher, but could not, as we used to say, teach their way out of a paper bag.

They would just, you know, they weren’t made for it. They didn’t understand it. No one ever taught it to them. And I swore to myself, I really did, if I ever get into that line of work, I am not going to subject students to the experience that was imposed on me all those years.

The job of the teacher is to make it understandable. And if you’re not doing that, you should be doing something else.

Eleanor Goldfield: Agree. And not just understandable, but enticing. And I never thought that I would be interested in economics, but I listen to your show and I think my old econ teacher would probably fall backwards out of surprise if he knew that. So, thank you.

Dr. Richard Wolff: My pleasure. Thank you very much, Eleanor.

If you enjoyed the show, please consider becoming a patron over at Patreon.com/ProjectCensored

Support our work over at Patreon.com/ProjectCensored

Mickey Huff: Welcome to the Project Censored Show on Pacifica Radio. I’m your host, Mickey Huff, with co host and now guest Eleanor Goldfield.

Today we’re going to talk about a new film that award winning filmmaker Eleanor Goldfield has just completed.

The film is called To the Trees. It highlights forest defense tactics in Northern California while calling into question our current relationships to nature, how we might reframe them, and why that’s vital to our survival and a livable future. The film’s also a call to action, a dedication, a promise, and a militant apology.

So Eleanor Goldfield’s joining us today to talk to us about her film, and we’ll unpack some of that. But let me give Eleanor a more detailed and proper, formal introduction. Of course, people in the Project Censored audience know Eleanor Goldfield as the co host of the Project Censored show. Today, she’s here as a guest because Eleanor does a lot of work.

She is a creative radical, journalist, and filmmaker, also a musician. Her reporting and work has appeared on The Real News Network and Free Speech TV, also, of course, other places like Mint Press News, Popular Resistance, Truthout. Of course, here at Project Censored, and many other places. Eleanor is the 2020 recipient of Women and Media Award presented by the Women’s Institute for Freedom of the Press. She’s also currently a board member of the Media Freedom Foundation here with us. Her first documentary was called Hard Road of Hope, covering past and present radicalism in the resource colony known as West Virginia, and I’m sure Eleanor will allude to that and talk more about where you can see her work, her films, that film actually garnered international praise, including Best Feature Length Documentary Award. You can also see Eleanor’s work as co host of the podcast Common Censored along with Lee camp.

Eleanor, I could go on and on reading more from your bio and all the amazing things you do, and again, that’s because I do want the Project Censored audience to know how broad your spectrum of creativity and your streak of independent journalism and your truth telling. It’s really riveting. It’s amazing. And it’s an honor to have you here on the program to talk about your work. So thanks for taking time out of your obviously very busy schedule to be on the other side of the mic, as it were.

Eleanor Goldfield: Well, thank you, Mickey. I mean, I kind of want to ask you to, if I can hire you as my PR person, because that was, I’m impressed by that intro.

Mickey Huff: Yes, well, I’ll certainly do what I can. But today, we’re going to do that just in a conversation about a really serious subject that I think you’ve done great justice to with the amazing participants in the film, the way the film was shot, the whole package really. It’s about 34 minutes long To The Trees, is that right? So it’s short.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, it’s an appropriate length like a little, a little snippet, you know, it doesn’t ask that much of your time, but I tried to pack as much in there as I possibly could.

Mickey Huff: Yeah, I really think that you did and you know the writing, the synopsis that you have drafted for the film too is very poetic, it’s very inviting.

And you start in your synopsis, ToTheTreesFilm.com folks can go and learn more there and we’ll talk about other places you can find Eleanor’s work artkillingapathy.com, the main site. But the, film site tothetreesfilm.com, you start your synopsis by saying “that’s what creates a sustainable system, a human’s engagement in a respectful and responsible way with land and water and air and animals. It can’t be extractive all the time.”

And your film looks at what’s happening in Northern California, my neck of the woods, literally, further north than where I was in Sonoma, you’re talking about tree sitters, you’re talking about clear cutting. It’s something that’s been going on for a long time, and a lot of folks I don’t think know the extent of the damage that’s been done to the ecosystems in places like Northern California, but why don’t you tell us a little bit, maybe first how you were drawn to the topic and then the process of filming it and what you’re hoping to achieve with it.

Eleanor Goldfield.

Eleanor Goldfield: Sure. Thanks so much, Mickey. So basically it’s a topic that I’ve been drawn to for a very long time. I grew up amongst forests and wooded areas, both in North Carolina and in Sweden. Obviously not redwoods, they’re specific to a certain area that I did not grow up seeing, but I first saw them when I was about 16 years old.

And I was like, like most people are like, what? This is ridiculous. They are, I mean, if you’ve never seen one, you can just Google it. And of course it won’t be like the real thing, but you will be astonished at the size of these trees. And when you’re walking through a redwood forest, you really do think that you’ve landed in middle earth or Narnia or other, some other, some other Tolkien-esque fairy tale or C.S. Lewis style fairy tale.

And I think that because they’re so gorgeous and because these places are on postcards for California and even for the United States, you’ll see them as like this poster child for we’re cool, and yet there is nothing against the law in clear cutting forests of redwoods, which include forests that are, that could be 2000 years old.

And, that is astonishing to people, right? Of course, we shouldn’t be okay with clearcutting forests that aren’t as beautiful as redwoods, but I think particularly this, this aspect that places that are this beautiful and places that seem to be protected, right, like the Avenue of the Giants, if you drive up that in Northern California through Humboldt County, it’s like, well, these trees seem very protected and very happy, and you would never know that just up the hill, hundreds of acres of clear cutting happening, and so what drew me to this was my love of Redwoods, but then also the fact that nobody, even people who live in Humboldt, you know, I’d be talking to some lady at the diner, and I’d be like, yeah, I’m over here covering this, and you know, they’re clear cutting, she’s like, they’re what?!

You know, people don’t realize what’s happening in their backyards because it seems so absurd. And you can take that, you can copy and paste this reality and the reaction to it anywhere, any ecosystem, people would be surprised, Oh, they allow dumping in that lake? I mean, it’s a classic American story, right?

Because we don’t have this culture, understandably, of letting people know what’s going on in their backyard. So that’s what really made me want to push this out there so that people could know what’s happening.

Mickey Huff: Yeah, it’s really remarkable. And some of the terms, some of the language that I learned about in the film was very visual, very descriptive.

You talked about this assault on the ecosystem being an uphill battle in every sense of the word. You talked about a particular company, Green Diamond, owning, some 400,000 acres of land tucked away on private lands, here’s the term “behind sparse beauty screens and an eco-groovy public image,” right?

That really kind of says something. And, you know, look, just very quickly, I grew up in western Pennsylvania in the woods which also were being clear cut and strip mined for limestone and coal, and I saw it happening, and they would just, you know, sort of do a Bob Ross paint job over it, and move on when it got too close to the freeway or the roadside, you know, kind of thing. And that’s what you’re talking about with beauty screen.

I too remember when I came to Northern California, it’s been over 20 years now, 23, 24 years. When I first walked through one of those forests, it was like, hey, wait, I grew up in the woods and this is not it. It is absolutely amazing to behold. And I do remember the first time being around a well over a thousand year old tree. And I mean, it’s literally breathtaking. It’s a riveting thing to be around that, to be present among just the energy in those kinds of settings. And I know some people may be saying, Oh, this is this sounds absurd, this sounds like a religious experience. You know, use whatever terms or phrases you want.

The point is, is that it’s something to behold in nature. It’s extraordinary. And we don’t have a great track record, Eleanor, in our country of treating nature in extraordinary ways, meaning, to revere and respect it.

Our extraordinary ways with nature are to conquer it or overcome it or control it or harvest it. And in the process, of course, of alleged progress and transformation, we leave in the wake of human development, great waste, and destruction, and that’s really what your film, I think so passionately captures.

You have some amazing people in the film, including activists, forest defenders, as they’re called, as well as the executive director and staff attorney for the Environmental Protection Information Center, or EPIC. I’ve been familiar with EPIC for years, along with Wheeler and the, their amazing work.

Can you tell us a little bit more about the process of the filming, and what you captured, and what these amazing people really, this story that they tell, and how you capture it?

Eleanor Goldfield: Sure. And first, just to speak to that point that you shared, Mickey, which I think is really important, people will kind of have this knee jerk reaction, like, oh, that’s ridiculous to suggest that you love a tree, and it’s like, is that really ridiculous, or is it ridiculous to think that you can conquer this tree, or that this tree is worth so little that you can chop it down when it’s It’s literally been there since Jesus Christ was born, supposedly.

So I mean, what’s more ridiculous, right? Like the total paradigm we have with nature, which is really based on our misunderstanding that we are separate from nature. And I think all of what we’re seeing with climate chaos is just climate, nature being like, actually, no, you’re not, and let me prove it to you. So there’s, there’s that aspect and –

Mickey Huff: Nature bats last. I’m reminded of that phrase that our friend, the associate director of the project, Andy Lee Roth, always says nature bats last.

Eleanor Goldfield: It’s actually in the film too. Marnie Atkins, who’s a member of the Wiyot Tribe says that nature bats last and she usually cleans up. And that’s, that’s very true. And we’re seeing that more and more across the globe.

And so that’s the other thing that I wanted to highlight is that relationship with nature. And of course, that’s based in capitalism and colonialism. And so the folks that I spoke with, they come from a diversity of tactics and a diversity in terms of their relationship with these spaces, right?

So you have forest offenders, tree sitters, folks who are actively engaged on the front lines in terms of they are literally putting their bodies between the chainsaws and the tree, and they do that through the tactic of tree sitting. And then you have Indigenous folks. In this case, I spoke to Marnie Atkins, who’s a member of the Wiyot Tribe, as I mentioned, and her perspective and her work, which is very much based on land back. As she puts it, you know, we never gave up our land. We never agreed to have it stolen away. So the way that she says we see ourselves as we are still stewards of this land.

And I think that’s the other point is she says stewards, right? Not owners. Like there’s that, there’s that paradigm again. Ownership suggests an abusive relationship, right? We can look at the US’s history. Slavery. The ownership perspective, right? But to say that you own property, that you own land, that is an abusive perspective on that ownership. But steward, if you’re stewarding something, that is a respectful relationship.

And you mentioned Tom Wheeler, and I love his perspective because it is, again, a diversity of tactics. He is not a tree sitter and you know he told me off camera he’s like yeah I can’t with the heights and I’m like yeah me neither, I tried it and I’m like okay, Eleanor’s ground support. I don’t do the heights.

But he is a perfect example of: I wanted to be a part of this fight and I realized I couldn’t be on the front lines, that’s not my thing, how can I engage in this? Well I can do the legislative and the judicial side of this, which is really important.

And as he highlights in the film, you can stall things for quite a while in courts. You can make life a living hell for the companies by throwing these legal precedents and saying you’re violating this law and that law and this and the other thing. And he also discusses that relationship that they have with tree sitters, that these folks can go into these places behind the beauty screens and then report back to EPIC about what’s going on.

So there’s this mutually beneficial relationship there that I think is also really important and highlights that the idea that even if somebody’s doing a tactic that you wouldn’t do or that you might not agree with, work with them. Because if your goal is the same, to protect the forest or to protect the lake or what have you, then working together is necessary. And not everybody can be in the same place, not everybody should be in the same place.

And so those are the perspectives that I shared. And of course, Marnie Atkins is more so the perspective of how we shift that relationship and also why Indigenous stewardship of these lands is so important.

Mickey Huff: Yeah, absolutely. And I want to get into a little bit more of that and maybe into some of the specifics of the film, just so our listeners can get maybe a broader understanding of the significance or the extent of the situation that you’re talking about because it is vast and the percentage of the forest that has been taken and it’s pretty significant.

And I think the beauty screens exist literally and metaphorically right there. A lot of folks that don’t live anywhere near these things have no idea of the vast vastness of the forest number one, but subsequently, they don’t necessarily understand the destruction and the fact that these kinds of forests don’t grow overnight.

You can’t just replace them. You can destroy them in an afternoon. And I think that that’s something that maybe you can help paint a better picture of to help people understand some of the folks in your film, the forest defender, Pat, Mugwort, and also of course, the tribal citizen, Marnie Atkins, that you talk about from the Wiyot Tribe.

And I think that that’s something that we should maybe unpack a little bit more with the specificity and also some about the company Green Diamond. Before we do that, very quickly, I just wanted to remind listeners you’re tuned to the Project Censored show on Pacifica Radio. We’re joined today by Eleanor Goldfield, erstwhile co host of this program.

Today Eleanor is on the other side of the screen in the mic. Because Eleanor is also an independent journalist, a creative radical, a filmmaker, and many, many more things. Today, we’re talking about her latest documentary film, To the Trees. You can see more at tothetreesfilm.com. This is a very important film that looks at forest defense tactics, specifically in Northern California, and also calls attention to our current relationships to nature, how we might reframe them, and why it’s really vital to our survival and a livable future.

And Eleanor, just before that break, you had mentioned, again, some of the folks you talked with in the film, and I wanted to maybe try to focus a little bit more on the perspective of the folks that are tree sitters, or forest defenders, and also an Indigenous perspective. You, I thought, did a really nice job earlier saying, Eleanor is not into heights and, and up in the trees. Julia Butterfly Hill, whom we used to know years and years and years ago up in the trees, and we would see her down on the ground in Berkeley on occasion. And I, we would just thank her and say, I cannot go up there. But there is a serious ground effort, as you say, that supports these people.

But let’s talk a little bit about what it means to be literally a forest offender in this way. And also being an Indigenous person working to reclaim nature, you know, in a decolonizing way, Eleanor Goldfield.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, absolutely, Mickey. And, I just want to go ahead and say that I can’t speak for, in particular, Indigenous peoples, but also current tree sitters, because I am not one.

But I can share the stories that have been shared with me, and I can share the perspectives that I’ve understood through that.

Mickey Huff: And they’re in your film.

Eleanor Goldfield: Right. And I say that, and I think some people are like, oh, semantics, but isn’t all of life and philosophy semantics, really.

So some people will say, oh, well, it’s just a silly distinction that you’re making. But I do make the distinction that I’m not telling people’s stories. I’m offering a platform for them to tell their stories because they’re not mine to tell.

So, with regards to tree sitters and forest defenders. So forest defenders include tree sitters, but there’s also a lot of different roles that happen in forest defense, and I mentioned ground support. So tree sitters will oftentimes be in the trees for a very long time, and especially with redwoods, because it takes quite a long time to climb 200 feet. It took me 45 minutes. Now I was a newbie, so I wouldn’t say to people that that’s the norm, but it takes, it takes a while.

So you’re not constantly going up and down, because that would just be silly. So you rely on ground support to get you more supplies, like, hey, I need some more water up here, or, hey, do you have a good zine that I can read, or something like that.

People on the ground are also doing recon, checking to see where things are happening, if there’s something happening, that they can then get people together and say, hey, we gotta go over here, cause they’ve started cutting something. The people on the ground also make sure, again, that that supply chain stays open, bringing folks, whether they need more rope or what have you.

So Forest Defense is, it’s like a little town, you know. They actually call it a forest village because you have a lot of moving parts that ensure that the people up in the trees are safe and have what they need in order to protect these spaces.

And with regards to Marnie, I interviewed a couple of folks from that perspective of the Indigenous land back, but Marnie did such a great job of putting this into an engaging and, and powerful way of remarking on it. And one of the things that she does is she compares the current capitalist colonialist paradigm to Gollum in Lord of the Rings, which my little nerd brain was very happy about.

You know, she talks about the way that we engage is this is mine, my precious. But nobody, if you think about it, nobody reads or watches Lord of the Rings and goes, I want to be like Gollum! Like that’s not how you’re supposed to engage with that story. And yet here we are and our entire system is engaged on pedestalling the Gollum type.

So her commentary is really about switching that paradigm, and of course, recognizing that that demands that we look at the traditional stewards of the land, and land back is a part of that. And I think a lot of people are confused about what land back means, like, oh god, are they going to send us all back to Europe? Like, no, no. Maybe some of them want to, and I don’t personally blame them, but, the idea is that the stewardship, the quote unquote ownership, as our capitalist brains would see it, would shift so that the land would then return to its historical stewards who do a better job of taking care of it, right? So that we might have a livable future, you know, just a small little tiny aspect, a livable future.

And there are several tribes in several states that have gotten land back and are doing an amazing job of reclaiming it and rewilding it and also getting into these cycles where humans are not removed.

I think that’s another thing and actually I interviewed somebody on Project Censored about this from Survival International that talked a lot about how like the Maasai for instance in Africa were forcibly removed to create conservationist spaces. But really what you’re doing is you’re ruining that ecosystem because the Maasai had learned over thousands of years how to be in concert with the ecosystem.

And when you remove a significant part of an ecosystem, what happens? It collapses. So these places are doing a lot worse because we are, again, trying to impose that mentality that humans are other than an ecosystem. And when we do that, those ecosystems suffer. So this Indigenous perspective also demands that we have a working relationship with the land.

And that does mean, you know, controlled wildfires. That means clearing some, certain trees, particularly invasive species. So it is not this totally hands off relationship. And I talk about that as well in the film, about how instead of looking at it as manifest destiny, manifest dismantling.

And the idea that all of the progress, quote unquote, that we’ve managed in this country via manifest destiny has also been a destruction. So how can we flip that on its head again and talk about a manifest dismantling of that destructive force and instead thereby have a better relationship with ourselves, each other and nature. And again, that small little aspect of a livable future.

Mickey Huff: Yeah. And I’m very glad you brought up several points there, which leads me to one other, and I know that you’ve considered this and anybody involved in this has been at least confronted by it.

You know, the Pacific Northwest is logging country. A big part of the economy, and this is again, right back to capitalism, was to just westward expand, manifest destiny, take the lands, displace Indigenous peoples, use the resources.

It really wasn’t until the late 19th, early 20th century until the mostly white male capitalist forces, industrial forces, kind of kicked back and said, Hey, wait a minute, we got to save some of this stuff. Teddy Roosevelt gets all this credit for pushing for conservation as you noted.

But there are people living in the Pacific Northwest that make a living off of this industry, through this industry. You did just mention there needs to be some management of the ecosystem, obviously one that’s clearly less rapacious and destructive. But how do we balance, or is there even any way to balance these forces of people, harvesting that forest, making living off of this?

I mean, these people that are then pitted against each other as enemies, and they’re often people from the same working class backgrounds. I know you uncovered this a lot in the Hard Road of Hope, and if people haven’t seen that, I strongly urge it, in West Virginia. You know, having grown up in that area, the story you tell in that film, it’s just very true in a grassroots way, those real conflicts and how people eventually work together to try to deal with these things.

How do you see any of that happening? Or did you see any evidence of that in, I mean, you were in Northern California, Humboldt, not quite completely, but certainly the southern end of the Pacific Northwest and the logging extravaganza that goes on there. Eleanor Goldfield.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, absolutely, Mickey. And I’m so glad that you brought that up because I think this is a point that some people will shy away from because they’re like, awkward, I don’t know how to, how do I square this circle? Oh god, environmentalists and workers are always going to hate each other. And I think this is a point, an intersection that we have to talk about because it is very frayed at the moment.

And I think that the, one of the tree sitters, Pat, and I should mention that tree sitters and forest defenders will often use fake names and they’ll cover their faces for safety and security reasons.

So I don’t believe that their real name is Pat or Mugwort. But you know, maybe somebody named their kid Mugwort and more power to them. But, so Pat actually talks about this in the film, the idea that they say I want to see restoration jobs, because obviously if you can pay someone to cut down a tree, why not pay someone to plant a tree or to restore an area?

But they also point out: I recognize that it can’t all just be about jobs, right? And it can’t be. But at the same time, as one of the characters in my first film, Hard Road Of Hope, says, you can’t just tell someone to quit their job. Because of course, unfortunately, we do still live in a capitalist system, and if somebody told me to quit my job, I’d be like, cool, what am I gonna feed my kid? Your well wishes?

So you have to understand that this is the reality that people live in. And maybe people don’t enjoy cutting down trees. I imagine somewhere deep down, it does feel icky, just like people don’t wanna work in torture farms, slaughtering animals in this horrific way.

So I think that it’s important to recognize that we should be approaching this not from a demonization of the worker, but a demonization of this system in which the worker finds themselves, and recognizing that you are also part of that system, and being demonized, right, in much the same way, like forest offenders are demonized for being terrorists or what else have you.

And again, like you said, Mickey, this is the pitting against each other: well, you’re a terrorist trying to, I don’t know, save a tree. And that’s a terrorist thing to do. Or you’re a terrible person because you’re cutting down a tree.

And it’s like, look, we are being played by the same puppeteers. Instead of comparing each other’s strings, why don’t we cut them and talk about how we can build something better, and I think that this is definitely a conversation that’s happening in Northern California, it’s a conversation that’s happening across the country.

The problem is that, unfortunately, these logging companies, these big companies, are still the main people, as you pointed out, Mickey, that are doling out the jobs. And so I think that first what needs to happen, and there are a lot of folks that talk about this, is a revolution in thinking.

Before we have that revolution on the streets or in the forests, you have to have a revolution of thought, because people need to be ready to put down the axe. Well, I mean, not that people use axes anymore, but the proverbial axe, and say, I want to do something different, and I want to create a space where a job in reclamation works.

There has to be that revolution of thinking first before we can actually try to build that space and try to make that viable. So I think that’s also what’s happening in places like Humboldt County and, and in West Virginia.

Mickey Huff: This is all well put.

What do you see as next steps if people see this film and they become more alert or aware that this is happening, maybe become more aware of your work and see what’s happening?

Again, I see a connection to the Hard Road of Hope as far as the connection between workers, the environment, the political system.

Where do you see this going in a way where people can actually work together, can create these kinds of solutions, can work more toward reclamation? How do you see that actually happening?

Again, just like the previous question I posed that I think you, you dealt with head on, this is usually where things peter out, right? Oh, the segment’s ending, we’ve got to go now. And then people are just kind of left with like, okay, now what?

But in a serious way, what are some things that people can do? Because again, you mentioned people aren’t going to always climb to the top of the tree. What are other things people can really do as part of this to change the way that we see nature, treat nature, and start acting like all of it is our responsibility?

Eleanor Goldfield: Absolutely, Mickey, and I’m reminded of a quote that I learned in harm reduction with regards to drugs was: meet people where they’re at, right?

If the goal is to try to get somebody off of drugs, you can’t just tell them drugs are bad, m’kay? That’s not the answer. You have to meet them where they’re at.

So when I went to West Virginia, understanding where people are coming from as former mine workers or current ones or, you know, old white folks who probably don’t think the same that I do about things, but I’m going to sit down with them and have a conversation, the same way that I did in Louisiana, where I sat down with people who voted for Trump and had a beer and talked to them about why they thought the way that they did.

And I think that this is in particular important work for white organizers to do because we should not treat poor, white areas as foregone conclusions to the KKK or to the extreme right wing. There’s so much work to be done in terms of planting seeds.

And also, I think a lot of people have this feeling like, oh yeah, you gotta explain to people because they’re stupid. No, no. People do not need to be told what oppression is. They feel it. But what needs to be shared, and of course you know this as a professor, is understanding the context, understanding the analysis, shifting the analysis. And I think that that’s very important work.

And I think that what needs to happen with regards to, whether that be Northern California or West Virginia is going into these spaces, like if you are a logger going into these spaces as something other than, and I think what they did in Atlanta was brilliant.

You know they went, when they first started this campaign, they had parties in the forest, they had forest walks where they looked at different mushrooms and different animals and critters. They were like bring your kids and we’ll do childcare in the woods. I mean it was brilliant.

They made the woods a community space, but we don’t do that a lot of times because we’re like, Ew, woods and bugs and things. It’s like, well, of course, if we have that perspective, we’re never going to want to protect these places because we’re going to be like, but they’re gross and snakes and things.

So we have to shift the way that we interact with these spaces. Go out for a walk and go off the beaten path. Don’t just stay on the little gravel road that they’ve made for you. Go out and get a little lost. And, I know it sounds corny, but we should also ask why it sounds corny, but feel yourself falling in love with these spaces.

Feel yourself getting in touch with those spaces, not in a hippy dippy way, in an actually very scientific way, understanding that we are part of these ecosystems. Learn more about the places that you live, the bioregions that you call home, because then, just like it’s your, you know, in capitalism, your home, your castle, you will be moved to protect it.

You’ll be moved to say, actually, I don’t wanna engage as a job in this way. How about we create a worker co-op where we plant trees instead, or where we reclaim this space that has been destroyed by, you know, fill in the blank industry. That’s the kind of work that can be done by first planting those seeds and meeting people where they’re at.

Mickey Huff: Yeah, that’s very well put and a stellar reminder. A good note for us to wrap our segment. Still so much more to say. In fact, opening the can of worms at the end here: one of the challenges I think to that we face in this country is the overdevelopment and suburban and exurban sprawl. Many folks that live in this country don’t have ready access to a nature that you’re calling attention to here.

And I think that then it’s difficult to instill in people the degree to which this is happening, the harm that’s happening in nature when people don’t have any real exposure to it personally themselves. In some sense, it’s an abstract and folks don’t really understand, I think maybe what they’re even losing because they haven’t seen it.

And again, that’s part of the bigger problem is that we’re destroying it fast enough that it’s amazing to say that there are people born in American cities that have never seen a redwood tree, never seen the forest, never seen gardens. I mean, and that’s again, that’s another topic for a much bigger kind of a program.

I actually have done a couple shows about that or on the national parks and, you know, isn’t that nice is kind of an afterthought. We saved the park over there. I mean, what you’re talking about in To the Trees is much bigger, much broader, but it also is a reminder that there are good people really trying to make a difference and protect our environment.

And I know we went the whole show without mentioning eco socialism, but…

Eleanor Goldfield: Well, and I think that that’s also a good point is that meeting people where they’re at includes being conscious of what you say. Like, if I walked into a space and was like, Hey man, my favorite people are all anarchists, they would never talk to me.

Mickey Huff: It’s Eleanor Eco-Socialism Lecture for the day.

Eleanor Goldfield: Right. And that’s, that’s another thing, we can call it Steve if you want to, but I think at the core, if we’re talking about that, restructuring that relationship, then yeah, eco-socialism, anarchy, whatever.

Mickey Huff: I like Steve. Steve is the name of the big hedge in Over the Hedge, right? That the forest creatures named it Steve because it was less intimidating.

Eleanor Goldfield: There you go. And I think there’s a good lesson there, right? Because in the United States, the words socialism and anarchism and communism have been so incredibly dragged through the mud that, I mean, it means something different to everybody and usually not anything good.

And yeah, I met somebody in LA who had grown up there and didn’t see the ocean until he was 18. And he lived seven miles from it. I mean, and that also speaks to access. Even if you are close to nature, can you get there? If you’ve ever lived in LA, you know, it’s nearly impossible to get anywhere if you don’t have a car.

So that is a great point. And I also think it speaks to the diversity of tactics. Like if you don’t have a forest in your backyard or a lake or an ecosystem that is being challenged, then you can engage in different ways. You know, there’s a, there’s a place for everyone.

Mickey Huff: Well, Eleanor Goldfield, I’m delighted we were able to talk about your latest project, To the Trees.

Of course, folks can learn more about it at tothetreesfilm.com. They can follow your work at artkillingapathy.com. And of course, they can tune in here on the Project Censored Show to hear your work as co host, as well as being a creative radical filmmaker, independent journalist, among the many other things that you do.

Eleanor, thanks for joining us today on the Project Censored show.

Thanks so much Mickey.

If you enjoyed the show, please consider becoming a patron over at Patreon.com/ProjectCensored

[/openrouter]

[openrouter]rewrite this title Capitalism: The Ultimate Anti-Life System[/openrouter]

[openrouter]rewrite this content and keep HTML tags

892

/

It all comes back to capitalism. In the first half of the show, economist, author, and show host Dr. Richard Wolff joins us to talk about empowerment beyond the strike, and how we can manifest true democracy in the workplace. He gives us a grotesque look inside the board room, the unfair imbalance between unions and corporations and how this affects us all, from stagnant wages to imposed inflation. In the second half of the show, Mickey Huff talks with co-host Eleanor Goldfield about her new film, To The Trees, which highlights forest defense tactics in Northern California while calling into question our current relationships to nature, how we might reframe them, and why that’s vital to our survival and a livable future.

Notes:

Richard Wolff is Professor of Economics, Emeritus, at the University of Massachusetts. He co-founded the academic journal Rethinking Marxism, and he hosts a weekly radio program, Economic Update. His website can be found here. For further information on Eleanor Goldfield’s new forest documentary, visit To The Trees Film.

Support our work over at Patreon.com/ProjectCensored

Eleanor Goldfield: Thanks, everyone, for joining us at the Project Censored radio show. We’re very glad right now to be joined once again on the show by Professor Richard Wolff, who is a professor emeritus of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

He’s currently a visiting professor at the New School University in New York. He’s also the co founder of Democracy at Work. info and its weekly radio and TV show Economic Update. Thank you. You can find more of his work at democracyatwork.info and rdwolff with two f’s dot com.

Dr. Wolff, thank you so much for joining us.

Dr. Richard Wolff: I’m very, very glad to be here, Eleanor. I really enjoy speaking with you.

Eleanor Goldfield: Likewise, thank you. So I wanted to ask you about the economics of this corporate hack of quote unquote tiered workers. This is something that we see cropping up all over the place. UPS workers were demanding an end to the two tiered system, they called it, that included a massive wage differential between full time and part time workers and between drivers and inside workers.

A recent post by A More Perfect Union outlines the way that temp workers at Jeep make half the rate of full time employees, though they do the same jobs, with some workers having been temp for more than five years with no clear path to becoming full employees.

So I wanted to start us off by asking you to talk a bit more about this trend, what it means for the corporations and what it thereby means for the workers.

Dr. Richard Wolff: Okay, I’m glad to do that. Let me just add that one of the key issues in the strike right now between the United Auto Workers and Ford GM and Stellantis is precisely the two tier system that was put in place a few years ago and is violently objected to by the workers.

Let me approach this historically, which will set the tone for it.

Karl Marx once wrote that the history of the world is the history of class struggle, whether it’s master and slave, lord and serf, employer, employee, it’s always the same. And what he meant was if you organize workplaces, like factories, or offices, or stores, if you organize them with a small number of people at the top, the major shareholders, the board of directors, the owner operator, and then below them a mass of employees, you’re going to have endless tension.

Because what the employer wants is the maximum profit out of those employees. What the employees want is a decent income to raise their families, to live their lives, to have what is nowadays called a decent work life balance, et cetera, et cetera.

And these are conflicting goals. The employer gets more profit the more he squeezes the workers. And the worker who’s fighting for better lives for themselves find themselves opposed by the employer who doesn’t want to give them that. This is a, a struggle without end.

And now we have the context. Two tiers is a way of engaging in that struggle and should not be misunderstood for being anything else. Here’s what it means.

The employers have figured out that they have a better chance of squeezing their workers to get more profit out of them by setting them against each other, by finding ways to provoke or to worsen, if they’re already there, arguments, disagreements, suspicions, all of it.

And we, we see it everywhere. Male against female. Older worker, younger worker, white worker, worker of color, and I could go on and on. But they’re creative. They don’t just deal with the old inherited conflicts like those I just mentioned. They’ve decided to add a few of their own, and one of them is the tiered worker system. Here’s how it works.

Workers now, working right now at this moment, whenever that moment is, are told by the employer, we don’t want to make life difficult for you. We will continue to pay you the wages that we’ve been paying you. No problem. All we ask is that you allow us to hire new workers when you die, when you take a different job, when you retire, whatever.

When we replace you, we want to have the right to bring in the young worker, the new worker, at a lower wage than we pay you. And, but of course, since we believe in democracy, we’re going to give you the vote in your union whether or not to accept doing this. Notice that no vote is given to the unknown people to be hired later.

So they, who might say, no, no, no, no, no, if I’m going to be doing the same work as somebody else, I want to get the same pay. They’re not allowed to vote by this little arrangement. Who does the voting? Only the workers that are there now, because they are the ones in the union who get to vote. Now, they may have a feeling that they don’t want to do to the younger generation what was not done to them by the generation before them.

Two tier is a relatively new gambit. So, a lot of those workers won’t go for that because they understand what I just said. But a bunch of others who don’t know their history, no one has taken them aside to teach them, no one is there doing it now. If you have a corrupt union leadership, it kind of goes along with all of this.

And at least immediately, the older workers won’t notice it because they’re continuing to get paid. So they are able, sometimes, to get one by on the employees who actually vote to accept the contract with two tiers.

As the United Auto Workers shows, once they understand and see it, once the older workers recognize the lesson, if you want those younger workers to go out on strike when it’s important for you, then you’re not going to get the kind of support you want if you have taught those workers not to trust you because you went along with a deal that gives them half the pay you get for doing the exact same work. And the same applies to temp workers, which is just another way of doing the same thing.

I like to talk about it not only to teach people not to be fooled, but because it’s a lesson. That the class struggle that our mainstream media avoid referring to on pain of near death, they’ll say all those seven words that Carlin told us never to say, they’ll punish that, they’ll deal with all, but to say class struggle, well that, that’s much worse than any of those seven words, which I know not to say.

The hypocrisy is grotesque here, but that’s what we’re looking at. We’re looking at Class struggle. In our moment of history.

And I think you’re seeing the United Auto Workers saying, no, fool us once maybe, you’re not gonna fool us twice. We’re not going to do this. We’re going to fight against that. And I noticed there are a number of other unions that are beginning to really push back. They’re learning that this is not only good for the employer, it’s bad for the union and all the solidarity that they would want. So they lose twice from this deal.

Eleanor Goldfield: Right. An injury to one is an injury to all. And since you mentioned the UAW, I’m curious what your thoughts are because there’s been a lot of back and forth with people arguing about the tactic of this partial strike.

And I’m curious, what are your thoughts on the partial strike as a tactic?

Dr. Richard Wolff: Well, I shy away from too much commentary on these tactics, and not because it isn’t an important topic, it’s just we can’t know.

The way these things are done, there’s a small room in some hotel somewhere where the representatives of the auto companies are sitting across the table from the union leaders of the union negotiating team, and probably in the room, either physically or spiritually, is a President Biden, and people should be very clear, he’s there because he’s worried about his election next year, as he should be, and he figures out he’s going to be in trouble, depending on how this strike goes.

So for example, and I’m not saying this is what happened because I don’t know, I wasn’t in that room and nobody who was in that room has spoken to me. So this is purely my guesswork. But here’s my guesswork that the union probably understood that its best leverage would be to take all 150,000 workers out at the same time, which is at midnight last Thursday. Okay.

Mr. Biden would have preferred a settlement, the way the Teamsters settled with the United Parcel Service a few weeks earlier. They compromised. What Biden got was, there will be a strike, you know, we’re not going to call the strike off. But what Mr. Biden got was this approach of, we’ll start with three or four plants, and if we don’t get a response from the employer, then we will broaden it out. That’s the kind of thing that often happens, because you really have all three.

The minute the union gets large, then the politicians, if it’s not the president, well, then it’s the senator or the governor, depending on the size and the number of voters affected and the publicity the thing gets. But that’s the way our society kind of works.

And the union may also have had other reasons. It’s very hard. People have to understand. It’s very hard to take workers out on strike. Remember the unfairness of it.

I’ll take just General Motors, for example. Their CEO, Mary Barra, you know, was revealed during the last two weeks to have a salary currently of $29 million a year. A salary that went up, on average, went up about 40 percent over the last four or five years. So, I mean, these people are rolling in money. Just rolling, number one.

Number two: the strike does not affect their income. They continue to be paid if the strike lasts two days, two weeks, two months, don’t make any difference.

Think how utterly different the other side of the table is. These are workers who are on strike because they’re not getting paid enough. Faced with the inflation, faced with the rising interest rates on the credit cards they all carry, etc., etc., etc., they are people that are being squeezed. And now, for every hour they’re out on strike, they lose money, because the strike pay from the union is significantly less than their pay.

So, they are taking it on the chin every day. And if you’re the union leader, even if you’re relatively militant sounding, as Shawn Fain, the new head just elected of the union is, you don’t want to take your people out and subject them to that. So you have to worry that a lot of workers are going to feel, rightly or wrongly, that you should have tried at least with a few factories at the beginning so that the others wouldn’t have to suffer if that would be enough.

So he’s going to wait a week, give the company a chance. That may be more acceptable to his members. All of those kinds of considerations are there.

But I want to stress the basic point. Labor management negotiations of this kind are really negotiations between David and Goliath.

And David is the worker and Goliath is the employer. And the question is whether the strike is a slingshot or not.

Eleanor Goldfield: A very good metaphor. And I’m also curious about that because you mentioned the Teamsters working to figure out this contract with UPS and a lot of people, particularly obviously on the left said, well, that wasn’t good enough. There was so much about the their demands that weren’t met. The rail workers ended up not going on strike thanks to, as you mentioned, Biden, basically saying that it would be illegal to do so.

And I’m curious about the class structure that also exists inside unions, you know, a lot of people were then pointing at the heads of the union saying, well, you didn’t push hard enough, you didn’t demand hard enough.

What is your perspective on that, understanding just as you said as well, that it’s a difficult thing to decide because pulling people on strike is also very damaging.

Dr. Richard Wolff: Yeah, I mean, union leaders are in a tough position. Are there some who are corrupted and basically serve as organizers of the workforce for the employer? The answer is yes, there are such union leaders, and therefore every union member in any union is always worried whether he or she admits it or not: are my leaders that way? And I hope not. That’s why there are hotly contested races, as there were in the UAW. And Shawn Fain, the new leader, who won by very little. We’re talking 100-150,000 votes. He won by 400 and some votes. So this was a, he’s got to show that he really is the better one, because an awful lot of people in that union are going to be skeptical, the ones that voted for the other side, which was more the traditional leadership.