[openrouter]Summarize this content to 2000 words

519

/

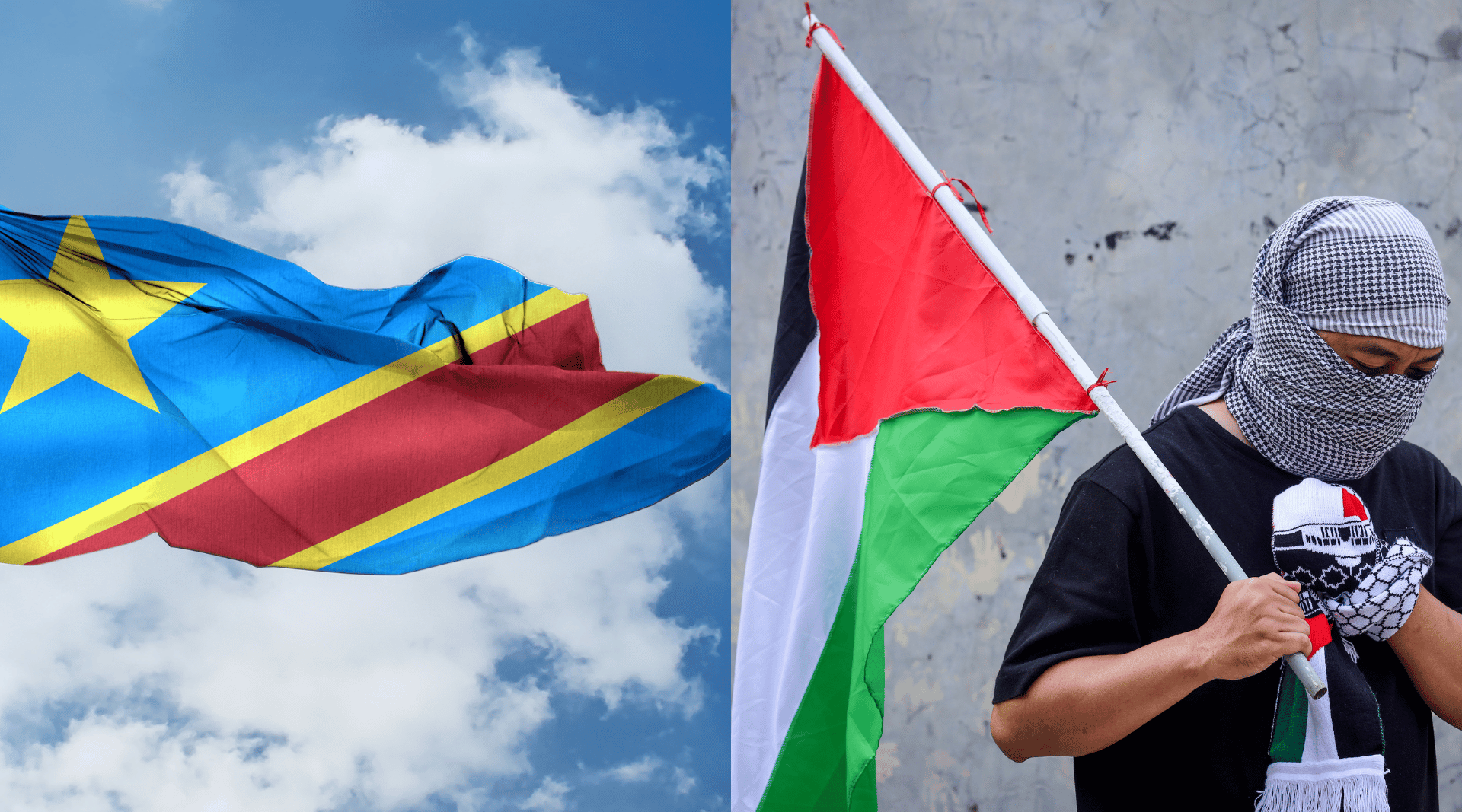

In the first half of the show, journalist and activist Eugene Puryear joins Eleanor Goldfield to pull back the curtain of imposed corporate censorship on Congo. Eugene highlights the myriad forces of green imperialism scarring both land and people as the Congolese find themselves in a crowded crossfire of countries and militias vying for rare earth minerals. He shares insight on the growing grassroots movements for justice and liberation as well as why corporate media won’t and don’t cover Congo. Next, cohosts Mickey Huff and Eleanor Goldfield cover a new report that shows how cable and social media respectively shift how Americans view the ongoing genocide in Gaza. They also dig into a few ways in which legacy media bury the lead, lie through omission, and seek to obfuscate facts, not least of all when it comes to the targeted killings of frontline journalists in Gaza.

Video of the Interview with Eugene Puryear

Video of the Interview with Eleanor and Mickey

Below is a Rough Transcript of the Interview with Eugene Puryear

Please consider supporting our work at Patreon.com/ProjectCensored

Eleanor Goldfield: Thanks everyone for joining us, the Project Censored Radio Show. We’re very glad to welcome back to the show, Eugene Pier, who’s an American journalist, author, activist, politician, and host on breakthrough News.

He’s also the author of Shackled and Chained: Mass Incarceration in Capitalist America.

Eugene, thanks so much for joining us.

Eugene Puryear: Thank you so much for having me back. Great to be here.

Eleanor Goldfield: Absolutely. And Eugene, we had you back on the show in October to talk about what’s happening in Congo. And I definitely recommend that folks check that out, especially if you want more backstory on the issues that place the Congo as a battleground for immensely rich natural resources internally, via Rwanda and of course, so called Western powers like France and the US.

And one might call it an epicenter of green imperialism. So, Eugene, I want to start with April of this year when Congolese President Tshisekedi met with French President Macron to discuss quote unquote mineral mapping, which to me, just takes me back to the Berlin conference, like the mapping of, the cutting up of Africa. It feels very similar.

He was also seeking investments from French companies in both agriculture and the energy sector. So could you talk to us a little bit about the ownership, the current ownership of these mines? Who’s responsible for this child and slave labor, and what investment from imperialist powers would mean?

Eugene Puryear: Well, you know, it’s a great question. And I think pointing to the Berlin conferences is a critical reference point because what’s happening in the Congo really is a scramble for resources and a scramble for wealth on multiple different sides. And the trip of Tshisekedi to France is a big piece of that.

So, you know, in the current moment, it’s a bit of a mix in terms of the mines in terms of the different minerals, but most of the sort of critical minerals in Congo are mines that are Chinese companies usually partnered with Congolese companies. But then there’s also a niche for a lot of Swiss companies, quote unquote, but really it’s sort of Swiss domiciled American, primarily American and European countries. And then also you have UAE involved in a significant way, especially in the issue of gold.

And so one of the issues that has become a factor is that the Western countries have become very concerned that China has in their words, a quote unquote, stranglehold on critical minerals for the future, primarily cobalt, but also nickel, which are critical for the batteries, essentially, that are powering our everyday lives, but also copper, which is also mined in relationship with nickel and cobalt, which is a huge part of all the wires that we use. So really that the things that are powering our everyday life, if you will, are not only concentrated in Congo, but that most of them are then mediated through China, right? So it goes from Congo through some other African countries to China, and then they’re selling it to Apple and so on and so forth.

And so they, the Western countries want to cut out the Chinese middleman, so to speak, and they want their mining companies to be in a better position. And so France, following the United States, which has been doing quite a bit on this front, the United States is funding a new big mining project on the border of DRC and Zambia, which is actually where some of the worst abuses are taking place. Some of the ones that no one really knows about.

Some people think, and I think credibly so, there’s actually modern day slavery happening in a lot of these areas because they’re so remote. No one knows exactly what’s happening. And this is the area the United States is trying to penetrate its companies and its capital into.

Then they’re also along with France, and this is a part of this trip, building a railroad from a very mineral rich region of Congo through Angola to the Atlantic ocean to make it easier for Western countries to get access to these minerals.

So, Tshisekedi going to France, and Macron, of course, giving him a big red carpet treatment, as it were, was very much tied into the desire of French companies to get into the game where the U.S. companies are, where the Swiss companies are, where the Australian companies are. Australia, another big mining power, which is trying to essentially edge China out from this perspective.

So, to go back to the quick thing, and I’ll end here. In terms of the agreements and the terrible state of artisanal mining, which is, you know, people are being poisoned by mercury, there’s all these mine collapses, people are being hurt. There’s no education for kids. Clean water is being completely destroyed. And the amount of money they’re making is like, it’s so negligible it’s almost a joke to even talk about in terms of what they’re making year to year.

But to say all that, another big piece of Tshisekedi’s trip, and this has also been a big piece of what’s been talked about for the past year in Congo, is this idea of investing in small and medium sized enterprises. Now, of course, that sounds good to a lot of people, like small business, that’s good. But what that actually means is they’re expanding the realm of essentially subcontractors that are Congolese to cover for these various foreign companies.

So they’re going in and saying, you give more money to this person and that person who is tied to the presidential administration to be a subcontractor on your project. So it won’t really be Congolese control of Congolese minerals, but more of the wealth will be funneled to Congolese elites. And there are very few rich people in Congo percentage wise, but numerically, a very significant number of millionaires that are coming from this sector.

So they’re trying to expand that sector. And these people are really the people who I think are the most responsible in some ways for the conditions on the ground, because since all they care about is money and all they care about is getting their contracts, whether you’re coming from China, whether you’re coming from America, whether you’re coming from Europe, they’re just like, whatever y’all want to do to get this out of here, do whatever you need to do. As long as you pay us off.

And the Congolese military and some of these various armed groups often support these efforts to make sure that these things are happening, and capitalism being what capitalism is, the bottom line rules everything.

So if you can get the minerals out super cheaply, you’re going to do it. So I think it’s really a very important factor of what we saw in France is that the elites of Congo are trying to get more from France in order to basically sell their own country for parts and they’re trying to play the different countries off against each other to get the maximum amount of money for themselves while almost nothing trickles down to the average person who’s mining or living in these regions, doing agriculture or the like.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, absolutely. And thank you for connecting those issues because it reminds us that we can’t talk about imperialism without capitalism and vice versa as well.

And I’m curious. I mean, we’re you’re talking about these mining regions. And of course, something that has pushed Congo to be discussed, not of course, on corporate media, which we’ll get to in a minute, but on alternative media sources is the extreme violence that’s happening there.

And as I understand it, and as you pointed out, this is part of this larger proxy war for these resources. And I also saw that earlier this year, the EU pledged 20 million euros to the Rwandan military to secure minerals for quote, clean tech and also a natural gas site for France. Just throw that in there as well.

At the same time, of course, uh, you have politicians like Macron talking about peace solutions for East Congo. And at this meeting between President Tshisekedi and Macron, a representative for the Congolese president cited France’s membership on the UN Security Council as, you know, a positive thing: oh, they’re going to propose resolutions for the DRC.

But as the organization Friends of Congo points out, the DRC has the largest presence of UN forces in the world, and there is reported evidence of mass violence by U.N. troops, which is also something that protesters were decrying last year at what became known as the Goma Massacre, where Congolese troops killed 56 people who were protesting the presence of U.N. forces.

I mean, it just seems like there are enemies on all sides. You’ve got the Rwandan military and militias. You’ve got the UN forces who people are saying have done extreme acts of violence. And then you have Congolese forces firing on and killing the Congolese for protesting this violence. I mean, it seems like a morass of just violent forces all trying to take control of the Congo, and the Congolese people not having friends anywhere.

Eugene Puryear: I think that’s a very good point. You know, it really all dates back to 1997. I won’t do all of the history, but just to give people a sense, you really had, and this is the long time pro Western, pro imperialist dictator Mobutu Sese Seko. He falls in 97.

And other than a very brief period, you essentially have had state collapse from then to now, and you’ve had this contest of various different forces in the eastern part of the Congo, especially trying to control territory because controlling territory means controlling money. And so there’s been all these various shifting sands over the years.

You also now, by the way, have a Southern African Development Community, a group of troops that are in East Congo that are fighting the Rwandan backed M23 rebels. Ironically enough, the Southern African troops are probably more popular in some cases than the Congolese troops, even though they’re from other countries, because many people see South Africa and some of these other countries as having defended, Zimbabwe and others, having defended Congo against Rwanda, at different times Uganda over the past, but nonetheless, still very similar issues that you have here.

But what it really all boils down to for the Congolese people is that they have been made essentially pawns by their own leaders and by leaders in other countries. And there hasn’t ever really been a political process that has allowed them to weigh in in any significant way.

Now, of course, there’s a lot of struggle on the ground that takes place. You mentioned the Goma massacre, people protesting. There’s actually a lot of protests in Goma on a regular basis, but they’re relatively small because there’s a state of emergency. So you essentially could be arrested and other things like that.

The artisanal miners are continuing to try to come together, create cooperatives to protest, to do different things, but still, nonetheless, it’s hard to find a political space because on the one hand you have the Congolese government, which most Congolese want the Congolese government to have, whatever their critiques of the government, to have hegemony over the country.

They don’t want all of these armed groups. They don’t want other countries coming in from outside. So you have people who want the Congolese government to take action and to try to control the area and to bring stability. But then you also have all of these various different armed groups. Some allied with the Congolese army, some relied with allied with Rwanda, and they’re also, they’re fighting each other for control of this territory.

And ultimately, there’s so many different mixed up issues that really exist in this context. There’s not an ability for either side to really win out. And so you’ve had for decades now, these sort of two general sides, you have sort of a government side and a Rwandan backed side and a number of armed actors with different motivations, aligning with either side to sort of war over this area.

But the thing that is clear is that on both sides, the main goal is to get control of the resources and not even really to get control of the resources. That’s actually not even the right way to look at it, but to become the interlocutor for the resources with the foreign powers of various sorts.

Right? So it’s is Rwanda going to control the flow of these goods? Is Uganda going to control some of the flow of these goods? Are the Congolese elites going to control some of these goods? Are they’re going to try to find some way to collaborate with each other? To come up with a plan where they can work together? But it’s elites on both sides trying to exploit Congolese mineral resources, and so they both conspire to keep popular resistance from really rising in any significant way in the eastern part of the Congo, which makes it very, very difficult to change the political balance of forces, although we’re seeing some green shoots.

I mean, in the last presidential election, you had an independent candidate, Denis Mukwege. It’s rare that someone outside of the sort of political elite system can make any noise. And he was making a lot of criticisms of what’s going on in the East. We’ve seen the Rwanda’s killing campaign by the Congolese, which if you watch international sports or events, people doing this [Eugene holds hand over mouth and other hand in gun shape to his head] and that image, which went around the world, which did so much to bring awareness to what was happening in the Congo.

So we’re seeing development of popular resistance, but it’s difficult when you’re sort of between a rock and a hard place here, where even the people who I think many Congolese hope win the fighting are in and of themselves, not really having an agenda that’s popular for the Congolese people.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, absolutely. And I’m curious because right now, especially with what’s happening in Gaza, a lot of people are hoping that the U.N. does something. You know, the I.C.J. will say this or the U.N. Security Council might do something like that.

And I want to temper that hope and that fervor for the UN with, why is the DRC the home to the most UN forces? And what are they supposedly doing there with regards to the unrest and violence?

Eugene Puryear: Yeah. Well, I’m glad you said it because we do have to temper our hopes. And now the UN is actually withdrawing because it’s become so unpopular. It’s doing it very slowly.

But the reason why it’s the biggest force is because since 97 and really even a little bit before that, the knowledge of what’s going on in Congo has prompted various countries to try to use the United Nations then the Security Council countries is in particular as a regulating force, and that perhaps the United Nations by stepping in could create sort of like a buffer zone that could establish some level of stability or security that would facilitate the flow of minerals outside of the Congo.

So they’re there for the exact same reason every other armed forces there. It’s just that it’s really the agenda of the big powers that are looking to find a way to make sure that this sort of resource extraction process can happen with the least amount of conflict possible and sort of stand in-between the two sides, but nonetheless, it hasn’t worked at all because it’s not addressing any of the root causes of what’s actually taking place in the Congo.

And it’s just asserting itself. And you have this weird mandate where, and listen, it’s unclear. Some of these UN forces are profiteering. Some of them are committing various crimes against the local communities. You know, oftentimes they’re not even fighting some of these other forces. It’s not like they were waging a super aggressive security campaign in the first place.

But even to the extent they were, the cause of it or the sort of reason for it is certainly not a benign reason. It’s just designed to create stability to help resource extraction. And so ultimately, they ended up getting caught in the morass of all these various groups and all these various interests and not being able to make a difference and ultimately becoming complicit in all of it.

And I think it’s like a lot of these UN campaigns we’ve seen in Africa, same thing in Somalia in the early 1990s, where, because there’s not really addressing the root cause issue, same thing with Haiti, by the way, since you’re not addressing the root cause issues, since you’re not empowering the local populations and people to have a role in their own security, you’re really just dropping more armed forces into a very volatile situation that cannot be resolved by force of arms.

Like these questions are not going to be resolved by force of arms. You have ethnic issues that date back to the Rwandan, what’s known as the Rwandan genocide. I mean, that’s a very in and of itself a controversial issue and how it’s played out. But like the context around that is a big factor in what’s happening here.

You have other ethnic issues that are also playing out that are happening here. You have the class-based issues of the poor farmers and miners and others who are looking to have a different dispensation of the economy vis a vis the elites that’s playing out here. And so all these things are really political problems that can’t be resolved just by war. And if they could they would have been resolved by now.

So throwing in the UN, throwing in Southern African Development Community, throwing in whoever you’re throwing in is unlikely to change the status quo issue in the eastern part of the Congo because it’s not addressing why you have these conflicts in the first place, and it’s not addressing the social relations that would be required for real stability, which would be to not only have peace, but to have justice as well in terms of those who are being forced into the mines or forced into subsistence agriculture.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, absolutely. Thank you for that. I think it’s important to recognize that the UN isn’t just this egalitarian force for good, that it sometimes is painted as, and I want to get to the media silence on this because there’s been some rightful indignation on social media and on alternative media outlets that while understandably what’s happening in Gaza takes up a lot of bandwidth, it doesn’t mean that, I mean, we can walk and chew gum at the same time. There is space to discuss, and importance of connecting these issues with regards to what’s happening in Gaza or Sudan or Congo.

And I was curious to hear your take on why is corporate media so silent about this, even when they’re willing at this point to give a little bit of room on things like Gaza. I mean, Rania Khalek who works with Breakthrough News was just on Piers Morgan. So that facade seems to be cracking, but the lying by omission vis a vis Congo is staying steadfast.

Why do you think that is?

Eugene Puryear: I think from a US media perspective, Africa is seen as a non-story. I think most of the US, I don’t wanna say the US population per se, but the way Africa has been presented to them, it’s always like it’s just a group of people fighting somewhere. Like that’s kind of the story of Africa.

There’s a lot of poverty in Africa and it all kind of bleeds in and seems the same. So I think for a lot of mainstream US media, it basically is a story that it’s good to cover occasionally if something major happens, like on May 3rd, when there is the bombing of the refugee camps in Goma by the M23 rebels. Okay. We’ll do a story about that, you know, or if something, you know, some major issues, some UN report, but the sort of day in day out reporting, I think that it’s the sort of racism that exists in these outlets that make them not really think that this is something that would be saleable to the public, to their audience.

I think there’s some other factors that may be involved. I mean, I think that to some degree, like anything it’s complex until you understand it. But I think there’s also a factor that like to actually get into the depths of what’s really going on, it’s too big a story.

It’s too long a story, who wants to listen to all that. So rather than try to break it down intelligibly, you just wait and do these big moments. I think there may be some reticence from an advertising perspective, because ultimately, who’s really complicit is the major corporations that are benefiting from this, that are making most of the money.

I mean, the mainstream media wants to cover China constantly. So if there’s any negative story about a Chinese mine in Congo, they will cover it immediately, but they won’t really cover the issue of conflict minerals. I mean, Apple saying they have no conflict minerals. I mean, it’s a joke. It’s a complete and total joke, and it’s well known that they’ve created all these organizations that literally monitor what’s going on, that allow them to get away from it.

So you start talking about that, you’re talking about basically every major corporation on the planet, in the US and Europe, that you’re taking on all at once, and in a sort of advertising based business, I’d have to think that plays at least some role. I don’t know if it’s a controlling role. Now, that being said, in the Francophone world, Congo is very heavily covered.

And that is because, well, one, it’s a French speaking country, but because in France, in Belgium, the sort of colonial heritage of the French, you have a lot of the diaspora that lives in these countries, and you have even a lot of the population who’s more aware of what’s going on there.

So in the French language media, you actually get a lot of coverage of Congo, but I think in the English language media, it’s seen as a non story. It’s seen as just more Africans fighting. It’s only good for an occasional story. It’s too complex for anyone to even care about it. And on top of that, if we really get deep into the story, we’re going to be getting into an element of our own elites who we need to pay us to put out this news that maybe is not worth it.

So when you put all that together, better to just cover it in flashes here and there rather than get really into it. But one thing I will say is there are a ton of journalists in Congo, almost all working in French. But if you’re willing to use all the translation tools that are out there, you really can follow people on the ground. pretty easily on social media and all across the internet.

So I want to shout out all the Congolese journalists who are working in the war zone and everywhere else doing great work because they really are there and a lot of them working freelance independent, struggling to make it, but, great work.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, absolutely. Where would we be without those frontline journalists? And as you were talking, I was thinking, I feel like part of it too, is this aspect of green imperialism. Like the corporate media would want to show, Oh, look, we have all this green energy for lithium batteries or whatever.

And then the imperialist side of that is so dark and despicable. How do you square that circle? Well, you just don’t talk about it.

Eugene Puryear: No, it’s huge. And it’s a big conversation in Congo because, you know, Congo has tens of millions of hectares of arable land that’s totally unused. I mean, I’ve seen 70 million, 80 million, 100 million.

Like it could really be almost one of the breadbaskets of the world in terms of what’s there. And there’s a conversation in Congo about whether or not they should be focused more on food sovereignty and agriculture and moving away from mining because the impacts of it are so negative. And when we talk about all these different pieces, I mean, the idea that you’re going to replace every gas combustible car with an electric vehicle is absurd.

There’s not even enough lithium and cobalt to even do that. So there’s a question of whether or not to lean into this new green economy. Because it’s dangerous for the people there. And it may be a false dawn in terms of what’s possible. Cause as we know, you need more public transportation and less cars, you know, we need different things like that.

And we need to be talking about how that plays into ethical mining. So this is something that has been discussed in the past couple of elections in Congo. It’s definitely a big piece on the ground. Like how do we actually square that circle of, if we want to save the planet, which we must desperately do, it’s not a zero sum game. And we could probably reduce the need for a lot of these minerals and also increase the human rights, for lack of a better word, around those who are working in these areas who that’s what they really want, in a way that’s more just and more sustainable.

But again, yeah, you’d have to talk about things that people don’t want to talk about in terms of the agenda that’s being pushed around a particular vision of climate change, which I think is important.

President Tshisekedi, whatever his faults, he made this point very well when they were putting up some blocks of the Congo forest for natural gas. And he said, listen, this is obviously bad for the environment. We know it’s bad for the environment, but we’re completely impoverished. And so unless you’re going to give us money to help us lift up our own people, what else are we supposed to do?

And it really raised the point of climate finance super sharply and how the global North, if we really want to be serious about this, we have to invest in the global South and empower them to put forward their own solutions so that they don’t feel forced to be, you know, making any deal possible for some mine or some gas thing, just so people can have an opportunity to get well water in their village.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, we like we love to point the finger at small nations that basically their greenhouse gas emissions equal like one platoon of the US military but it’s their fault, you know, because they don’t know any better.

And I wanted to, because you’ve mentioned a couple of times elections and you mentioned grassroots, I want to get to that before we wrap up here. Because you had also shared and I saw this that there were some miners that were demonstrating in the mining capital, so called, of Kolwezi and basically calling for like a co op, basically, for the miners to own their own means of production.

And I’m curious, what is the status of these kinds of movements, particularly with the fact that massacres have happened for people just peacefully protesting, and with that, what are the chances of us seeing someone like a Patrice Lumumba come to power in Congo?

Eugene Puryear: Well, you know, I think the movements of miners, especially, but also farmers in the cooperative space, it’s nascent, but growing. But this is actually becoming a bigger trend across Africa because the artisanal mining, to even be able to bring in more mining technology, all these different things, you really have to band together.

And so I think what we’re seeing in DRC is, and what you saw in that protest, it’s nascent, but we’re seeing more and more of that. We’re seeing some of that around the gold industry as well. There’s in a way, it’s sort of a proof of concept in Zimbabwe where they actually set up a Zimbabwe Miners Federation where thousands of mainly gold miners, but some others, have banded together in a co op.

So if you want to come buy gold, you go to the co op and then they basically then interface with the miners. They gather up the amount of gold you need, and then they sell it to you. Then they redistribute the proceeds amongst themselves. So it allows you not only to band together to control pricing, but also to give yourself the means to improve the situation that you are in by bringing in more safety technology, by being able to build things in your various different mining fields, bringing in more advanced technology. Burkina Faso has been having a conversation between the government and artisanal miners around this. So I think what we’re seeing in DRC is very much in the vein of what we’re seeing everywhere.

But like you said, it’s difficult. I mean, you have these massacres and you have so many interests that do not necessarily want to see this, but because of the popular pressure, you’re seeing more of this happening. So there’s a gold deal between DRC and UAE that at least allegedly is supposed to also facilitate the growth of some cooperatives in that sector.

So, we shall see, but I definitely think the tide of popular resistance is rising. It’s just very challenging. But the fact that there’s more eyes on Congo is also helping because it’s created, there’s sort of conspiracy of silence around the suppression of these movements, even though it’s not anywhere we need it to be, it’s been broken at least a little bit, it’s cracking at least a little bit. And people are knowing these different actions are happening.

And in terms of the future. I think it’s possible. I mean, the Congolese political scene is all controlled by elites like almost everywhere else in the world, right? But on the same token, if you look at the discourse of the elites in the last election of all the different political parties, they’re all saying the same thing.

And they’re all in some ways, speaking to this. We need more development. We need roads. We need hospitals. We need schools. This is partially why, by the way, Congo is working so closely with China because a lot of these mining deals come with hospitals. They come with roads, they come with railways, they come with other types of infrastructure that people really need and want to see.

So even the elites who I think don’t want to make big pushes on this, Tshisekedi has made a bigger push than his predecessor Kabila. They have to speak to some degree to these popular aspirations. And that to me says that the sort of subterranean fire that’s happening amongst the average Congolese is scaring the elites to such a degree that they at least have to pretend that they want to move in that direction.

And that to me means that you really can open up the possibility for new political forces to emerge. And I think the legacy of Lumumba is very important, very well known. The young people especially are talking about Lumumba. They’re talking about Sankara. They’re talking about the history, just like all over the African continent.

So I think as bleak as it can seem, big change often happens sadly in very chaotic moments. And I think the people of Congo are interjecting themselves more and more into the political conversation in a way that’s harder and harder for the elite forces to ignore. But of course, that means that we’re going to see more and more, especially coming from the West, to try to prevent that from taking place.

Eleanor Goldfield: Absolutely. Thank you so much for all of that, Eugene. I really, really appreciate you contextualizing this important issue. I know you mentioned the frontline journalists. Where are some other places where people can follow this issue? And also, of course, your work.

Eugene Puryear: Well, you can definitely follow us as follow us at breakthrough news on all your social media @ BTnewsroom.

We’re trying to follow Congo as well. You can find me @ EugenePuryear. I’m trying to follow it as closely as I can. There’s a lot of local media, like I said, that’s out there. It’s all in French, so if I try to pronounce it, it’s terrible. But if you go to my Twitter, @ EugenePuryear, and just search Congo, search DRC, you’ll see I’m quote tweeting and linking to a lot of these on the ground journalists, and a lot of the local media in terms of my own work and that can kind of take you down a little bit of a rabbit hole to some of the radio stations, TV stations, websites and others, and also the journalists themselves who are working super hard to get this information out on Congo.

Eleanor Goldfield: Awesome. Thank you so much, Eugene. Really appreciate you taking the time.

Eugene Puryear: Thanks for having me.

If you enjoyed this segment, please consider becoming a patron of our work at Patreon.com/ProjectCensored

Below is a Rough Transcript of the Interview with Eleanor and Mickey

Support our work at Patreon.com/ProjectCensored

Mickey Huff: Welcome back to the Project Censored show on Pacifica Radio. I’m your host Mickey Huff with co host Eleanor Goldfield. This segment is another one of those where Eleanor and I talk about things happening around the world, things happening in the world of independent media, particularly focusing on stories that the corporate media either don’t want to cover at all, or as Eleanor is going to talk more about, when they do cover it, they have a wild spin and slant and they leave out important details and context.

And that’s why independent media is so really important. Eleanor, it’s always great to be in conversation with you. I know we’re often on our co hosting duties talking to other folks, but it’s always wonderful to talk with you and really to hear your perspectives.

And you’ve got several stories that have been really important of late, some stuff from our friends at Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, of course, The Intercept. So let’s jump into a couple of these stories, and let’s talk about the things that the corporate media would rather we not.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, absolutely, Mickey. And so, this is a poll, actually, that was done of a thousand people, so not like a massive poll, but still interesting in that little microcosm that mirrors oftentimes the macrocosm.

It was a poll done of a thousand adults conducted by a group called JL Partners from April 16th through April 18th of this year. So about a month ago, we’re recording this on May 16th, and it was paid for by the YouTube based news network Breaking Points, which is connected to The Intercept. So I’m, right now I’m pulling from an article on The Intercept, and it shows that cable news viewers, what we call legacy media or corporate media, are more supportive of Israel’s war effort, less likely to think Israel is committing war crimes, and less interested in the war in general.

People who get their news primarily from social media, YouTube, or podcasts, like y’all listening to this one, for instance, generally side with the Palestinians, believe Israel is committing war crimes and genocide, and consider the issue of significant importance.

And we can step into what can be gleaned by this, but basically the ultimate takeaway from this is that if you watch corporate media, you are getting the propagandized Zionist perspective.

And I’ll also be pulling from a Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting report specifically about the New York Times, which of course is not cable news, but they’re part of that, I’d say the Zionist propaganda conglomerate, and so basically those who focus on that kind of news are not seeing what’s really going on in Gaza.

But as we’ve talked about on the show before, this is the first genocide in the history of humanity that’s actually been able to be livestreamed. And that’s not livestreams that are showing up on CNN or Fox News, right? These are livestreams that are showing up on TikTok. Of course, that precipitated the push to shut down TikTok in the U.S. On Instagram, on Twitter, or X, or whatever we’re calling it these days. These are things that people are accessing through social media channels, and through podcasts, like the Project Censored podcast. So that is where people are seeing what used to be called just regular reporting, but now we have to qualify it and call it frontline reporting because reporting is just things that the corporate news networks purport to do.

Mickey Huff: Yeah, pretty amazing. The article too in case folks want to follow along, a Ryan Grim piece from the Intercept: cable news viewers have a skewed attitude toward Gaza war survey finds, a tale of two Americas.

And you know, Eleanor, we’ve seen many efforts over the last couple of years, and this is under a Democratic administration, under the Biden administration. We’ve seen many efforts by proxy or otherwise to curate, influence, squelch certain kinds of things that happen on social media.

And, we’ve talked at length on this program too, about problems of social media, screen addiction, data harvesting. I mean, there’s a whole raft of, of other issues that we talk about, but there’s also other reasons that social media has been significant historically, even if it’s in its more infancy technologically. It’s often a way to get reports and get things happening, like you say, frontline reporting. It’s a way to get information that’s happening that doesn’t usually make it through the filters of the corporate media or the corporate press.

And so, interestingly, our Congress, as our listeners likely know, voted to ban TikTok. Interestingly, in these hearings, they’re all talking about how TikTok is horrible and all the things that they do, and all the other things that they’re crowing about that are so terrible are all the same things that Instagram or Facebook or Threads or whatever they are. They all have the same issues. But TikTok is owned by a Chinese company, ByteDance. So the US government doesn’t seem to have enough proxy influence on it. And gee, a lot of young people seem to be getting information on these platforms that contradict or point out things that the corporate media, the legacy media, just aren’t getting at, aren’t covering, or are trying to play down or deny.

And so look, it just came out recently, and I think you and I maybe even have mentioned this before, Mitt Romney, you know, one of the quote, moderate Republicans still around quote unquote, they openly have talked about how the TikTok ban was because of Gaza, the TikTok ban was directly related to the things people were getting from it because they can’t control it.

You know, it wasn’t long ago that the editor in chief of the Wall Street Journal was at the World Economic Forum bemoaning the fact that people were becoming more media literate because, in her words, they couldn’t control the narrative anymore. I mean, she’s saying this out loud. We see people in Congress saying out loud the reason they’re banning it is because of the content.

Look, and even if they can skirt First Amendment issues and free press issues, which is an abomination, but we do have legal precedent and prior restraint and censorship by proxy is a thing, but it’s not subject to the legal regulations.

And so what we’re seeing right now is, I think, an open, hostility towards specific social media pattern outlets based on content.

And then, of course, what you just talked about with this article is that the kind of information that people are getting from these different sources does seem to have some role or impact on what their views are about things. And so, from a media literacy perspective, we should be merging a lot of these different sources so that people become more aware of what kind of, what kind of angles and perspectives are coming from where so people can be in their own driver’s seat and they can decide which sources are accurate in speaking to them and so on.

And look, we’re living in an era of deep fakes and fake news and moral panics. And well, I guess we’re also living in an era of as you said, what looks like a genocide happening in real time before our eyes that the corporate media is dancing around, but the social media platforms and people there are calling it out.

It’s creating a real crisis, I think, both for legacy media and our so called democratic institutions, because our quote unquote leaders or quote unquote representatives are basically fretting that they’re losing control of the narrative. We have a majority of young people think that what’s happening in the Middle East is flat out wrong.

And this is a very dire development in an election year when we have the team red team blue dynamics already afoot, and we have one candidate that’s talking fascistic administration. And we have another one that’s fiddling while, you know, the proverbial Rome burns and they’re dropping the bombs to light it ablaze.

So, Eleanor, we’re living in an interesting time and I think that, I think that you’re calling attention to this piece in the Intercept is exactly the kind of analysis that we would do here at Project Censored, and again, this doesn’t mean the Intercept is perfect anymore than it means the New York Times always lies, but we have to always say that because people are like, well, you’re blinded to this and you don’t pay attention to that.

Help us out. Listeners send the hate mail, but again, I think that it’s important. And then the other piece, Eleanor, there was another FAIR study?

Eleanor Goldfield: There was another one Mickey, but before we touch on that, I actually wanted to touch on a couple of things that you brought up, which is the election year and the age aspect. And I want to point out that, as you mentioned, a truly free press and an independent press would make sure that people can have access to all of these different sources and make up their own minds and have this critical media literacy lens and, you know, I, something that I found interesting was that just 8 percent of the people said that they got most of their news from print journalism, and that includes articles online.

And I found that interesting because it also highlights that while a lot of people aren’t reading these articles, as Ryan Grim does point out, which I’m glad that he did, news is an ecosystem. And so a lot of people that aren’t reading the articles themselves then get them through commentary, like what we’re doing now, right?

We’re reading the articles, so you don’t necessarily have to. Or through, you know, other people on YouTube or other podcasts, or even other TikTok and Instagram will comment on things that they’ve themselves read. So this also highlights the fact that what you might be watching if you’re listening to this, you are in fact getting something from print journalism, just not directly, and it shows also the importance of people who take a bunch of stories and then share that via podcast or what have you.

But I wanted to get to the age aspect because it showed that in this survey, people age 18 to 29 felt that there was a genocide being committed by Israel. Those over 65 by a 47 to 21 percent plurality said Israel is not committing a genocide. And of course, this also goes along with who’s more likely to watch cable news versus who’s more likely to go, not just primarily, but sometimes only to social media in order to get their news.

And so that was a huge, perhaps not that surprising, but because it also aligns, of course, with the college campuses being where so many of these protests are happening, right? They’re not happening at assisted living facilities, although I would love to see that. Grannies for Gaza. If nobody’s done that yet, please do.

The other thing that kind of went along with that, and I’ve seen this a lot with even when I was in my late teens, early 20s was the feeling of the propensity to vote. The feeling that your vote matters in a federal election. I’m not talking about local and things like City Council, but on a presidential level, whether it matters.

Because the thing is, both candidates are pro genocide, right? One’s actively committing it, and the other one says he would go even further. So you have no candidate, no real candidate from the two party system that is saying that they would stop it. So this is also, I think, pushing people to feel that, well, why should I bother voting?

And it turns out that print readers and cable viewers were by far more likely to vote. Those who got their news from social media or YouTube were most likely to say that they were definitely not voting or unlikely to.

And this speaks to not just this critical media literacy that pushes people to see what’s actually going on, but then to also dissect and analyze the system that is putting forth, quote unquote, different candidates that end up being very much the same.

And that then catalyzing a feeling that voting is not civic engagement, voting is not a proper way to engage with trying to change the world around you. Perhaps other ways of activism are, like college encampment or something like that. So it’s really interesting to see kind of this domino effect that is happening and also how these things are inextricably linked here, Mickey.

Mickey Huff: Absolutely, Eleanor. And, just speaking to that issue very briefly, and then I know you wanted to go on and talk about a recent piece at FAIR on how the New York Times was not much concerned about Israel’s mass murder of journalists, which is a really dire story.

I also understand the disillusionment particularly from young people kind of looking at what’s happening and trying to make sense of it. I would suggest, and hope that younger people in that category who are maybe feeling this kind of alienation to remember that there are areas of difference between the parties when it comes to some issues around the Supreme Court or reproductive rights. And, there’s a raft of issues where there are some significant differences.

And one of the things that I am concerned about as an educator is that because so much of this chaos is afoot and because there are such low opinion polls about our institutions, including the media, I worry that young people who should be hopeful and full of energy and optimistic, I think they’re getting turned cynical, and I think that being cynical at a young age is problematic for so many reasons.

Being skeptical, and we’ve talked about this too before, being skeptical and suspicious of our society and our power systems might spur more engagement and watchdogging, as it were. If we’re cynical, it just means people kind of tune out and let the grind go on in the direction it’s heading, which is not good.

And so, you know, I would hope that maybe through independent media and wherever people are accessing it, you said many younger people aren’t going to the print per se, but they’re learning about stuff through social media. This is why there’s a lot of focus on trying to curate or censor social media because it’s a place where it breaks the filters of the corporate system. It does allow for stories to get through.

So I would hope that for younger folks listening to this kind of program, I hope they would go to read these alternative and independent sources, whether it’s the Intercept or Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting.

ProjectCensored.org has a huge list of independent sources. You never know when someone’s going to accidentally tune in or roll by the radio dial and hear a conversation that they’re not hearing anywhere else on the dial. And so, hopefully, young people might take that to heart and realize that becoming more informed might change the way they’re engaged.

And voting is one way that people are engaged, but there’s a lot of other ways that people can be engaged in the system. And of course, Eleanor, you know that so well from your work doing direct action and the other kinds of work that you’ve done for years. And so I would, you know, again, I would encourage young people to be engaged.

We’re seeing a lot of that on the college campuses, right? That’s a significant engagement that I think is hopeful that people do care, young people are engaged and that they are not tolerating what the corporate media wants to normalize.

And that’s kind of what we’re getting at maybe into the next story, Eleanor. I believe the story that you were talking about, Harry Zehner, is the May 1 piece on the New York Times.

And I mean, again, we just saw the press index come out. The United States is down to 55th. Israel was down, I think, to 101. This is just preposterous, you know, that we talk about these quote free societies and Israel’s the beacon of democracy in the Middle East.

By the way, the Economist Democracy Index puts the U.S. as a flawed democracy at 29th, and Israel as a flawed democracy at 30th place on their index. Always worth repeating, right?

But tell us about this issue that’s been happening about the way the corporate media is or isn’t covering, you know, the Committee to Protect Journalists talking about record numbers, horrifically record numbers of journalists being killed in this past year, a majority of them in Gaza.

Can you talk about that in the corporate media framing or ignoring of that, Eleanor?

Eleanor Goldfield: For sure, Mickey. And I want to preface this by saying that the New York Times has several times highlighted that journalism is not a crime. With regards, not to people like Julian Assange and not to frontline journalists in Gaza, but for instance, Evan Gershkovitch, who was detained in Russia, quote, jailed in Putin’s Russia for speaking the truth, there was oodles, oodles, oodles, oodles of coverage of this, of course, because evil Russia bad.

This is Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, by the way, found that the Times wrote just nine articles focused on Israel’s killing of specific journalists, and just two, within, this is a six month span, so I’m not talking about like a few weeks, when dozens of journalists have been killed. I’m talking about six months here.

Just nine times, and just two, articles which examined the phenomenon as a whole. Of the nine headlines which directly noted that journalists have been killed, only two headlines, again, in six months, named Israel as responsible. So we’ve talked on the show before, we’ve had folks like Alan MacLeod who does a lot of work on the use of the passive voice, like, well, these journalists died. Of what? Of tuberculosis? What killed them? This is at best journalistic malpractice, and at worst, of course, it’s just propping up the propaganda machine.

And both of those headlines though, that named Israel as responsible, they put it as an accusation, not a fact. So for instance, this one that I’m looking at here says from the New York times on November 21st of last year, “pan Arab news network says Israeli strike killed two of its journalists.” Oh, they said so, did they? And yet, of course, if it were the IDF saying that something happened, the headline wouldn’t say, Israeli occupation forces said this.

Mickey Huff: No. I mean The New York Times is running, these outlets are running their stories through the Jerusalem bureau. They’re running it through IDF censors.

Eleanor Goldfield: Right. And I’d like to point out that, like I mentioned with Evan Gershkovitch and, I’m sorry if I’m mispronouncing this, but Alsu Kurmasheva, two U.S. journalists were being held in Russia. During that same six month period, The Times wrote nine articles, so the same number of articles on two journalists as they did about more than a hundred journalists that have been killed by Israel in Palestine. The same number of articles, and I’m willing to bet that those articles that were written about these U.S. journalists were very clear on whose fault it was, right? There was no passive voice used there.

And also with regards to these articles on the journalists in Palestine, the way that things are framed, even when they talk about blame and talk about fault, it’s still skewed.

So for instance, I’ll just read this, this is a November 4th article from the New York Times. “36 news workers, 31 Palestinians, 4 Israelis, and 1 Lebanese, have been killed since Hamas attacked Israel on October 7th.”

So right there, you have these people have been killed since Hamas did this terrible thing, so you’re still making sure that people understand or you’re trying to get people to understand that these people would still be alive if it weren’t for October 7th, October 7th, October 7th.

And so even when you’re willing or able to put down the fact that Israel killed these journalists, it’s just because of October 7th, right? And the other thing that they do is they blame the war. So instead of saying Israel killed someone, it’s the war, it’s the war that has killed these journalists.

What war? And what precipitated it? And as Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting points out there’s no mention of Israel’s long pattern of targeting journalists. And as you pointed out, Mickey, they also have included IDF spokespersons that of course say, quote, Israel has never and will never deliberately target journalists.

Cool, IDF spokesperson. We’ll just take your word for it. Shall we?

Mickey Huff: It’s extraordinary, Eleanor.

And, you know, the same piece at FAIR, and again, listeners here should certainly know FAIR.org, Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting. This is extraordinary, so I wanted to read it. According to these reports, Israel has killed more journalists in a shorter period of time than any country in modern history.

The Times has minimized when not ignoring the mass murder. Conservative estimates from the Committee to Protect Journalists estimate 95 journalists have been killed in the Israel Gaza conflict since October 7, all but two being Palestinian and Lebanese journalists killed by IDF, Israeli Defense Forces.

Other estimates from the Palestinian Journalist Syndicate place the number closer to 130. All told, Israel has killed about one of every 10 journalists in Gaza, which is a staggering toll. Two Israeli journalists were killed by Hamas on October 7th, according to this study, according to Committee to Protect Journalists. And there were two others killed as part of the audience.

So I’m not pretending that this hasn’t affected other journalists and this is always a tragedy, but is it not clear to you, Eleanor, that this is a very lopsided and skewed affair? I mean, the thing that’s striking to me is that killing more reporters in a shorter period of time than any country in modern history. That should be a headline at the New York Times. And then that should trickle over to cable, as you say.

Eleanor Goldfield: Right?

Mickey Huff: The print should lead, but the print should lead with the stories that we really need to hear. And, like you said, from that other piece, the Ryan Grimm piece, if, depending upon where you’re getting your news, this is news to you.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, absolutely. And, I mean, it’s despicable regardless, but then the fact that the New York Times frequently shares information about these two journalists who were detained by Russia over a year ago, talking about how journalism is not a crime and we have to stand up for our journalist buddies and our colleagues.

It’s like, okay, but I guess only if they’re white? I’m having a hard time following your thread here. By the way, Julian Assange is also white, but I guess, you know,

Mickey Huff: We have to draw lines here. Somewhere, right?

Eleanor Goldfield: We have to draw a line somewhere. And it’s clear that if you are reporting on anything that goes against Empire, if you’re reporting on anything that goes against the Zionist propaganda line, then you are not considered a journalist by the New York Times.

And it’s just so clear when you have that critical media lens, it’s just so clear that you’re being lied to, and when you have that ability to read these headlines, like that FAIR points out, and folks like Alan MacLeod, the use of the passive voice, you start seeing it everywhere.

And then, again, like the facade really begins to crack, and I think that’s, connecting back to that first article, that’s clearly what’s happened here, is that people, predominantly young people, who are oftentimes told that they don’t know anything, and, oh, you’re just too young, know more than the old people, like, clearly have a better handle on what’s actually going on than folks who predominantly, or only watch corpcorporate media.

And this, of course, goes back to what you pointed out at the beginning, Mickey. The corporate media does not exist to inform people. It exists to control people, and control the narrative and not teach us how to think, but exactly what to think in service of the system, the status quo.

Mickey Huff: Yeah, and there’s another part of this FAIR piece that says nearly all the journalists who have died in Gaza since October 7 were killed by Israeli airstrikes, according to the committee to protect journalists. And as the article at FAIR points out, we had to wait until the 11th paragraph of the story on the 116th day of the slaughter for the New York Times to finally publish that admission.

So, and the reason I’m pointing this out, and this is important. It’s not such that the corporate media never cover the issues or some of these stories. And this is the clever part. They’ll eventually, perhaps, maybe, get around to begrudgingly acknowledging something, and they’ll totally bury the lead. And if you read the headline, the headline suggests one thing, and then you read down the article halfway, and you’re like, wait a minute. The material in the article seems to contradict the headline, or it says something far more important than the headline implies, and this is a way that corporate media frame those stories.

And we’re back to that issue, and you mentioned that earlier, Eleanor, about how these stories are framed and what’s left outside the frame, but the folks at the New York Times can just go back and they can say to us, hey, we covered that story on January 30 in the 11th paragraph on day 116 of the slaughter. So we’re good. Right. We’re not censoring it. We’re not hiding it. We’re reporting it. There’s just a lot to do.

So this goes back even to the founding of Project Censored when Carl Jensen talked about news judgment. That the editors that are making these decisions and the powers that be that are pressuring them to do or do not cover stories.

That’s the news that doesn’t make the news. It’s the news about the news that the news never gets around to reporting. And that’s where often the devil lies in the details.

So the FAIR article shines a lot of light on this story, but Eleanor, it’s a very ugly and sad story.

It’s a horrible story about how many people are being killed, not just journalists. I know we’ve been focusing on that. But look, you know, we even see disputes coming up on the number of dead and in the UN when they declared that they’re trying to get an accurate count here, right wing media and neoliberal media climbed all over it. They were like, Oh, see, you’re over-counting it. It’s not that bad. It’s not 35,000 people. It’s only 20,000.

I mean, I don’t understand the logic, but you know, somehow we’re all supposed to kick back Eleanor and say like, Wow, man, I thought we were on the way to genocide. Fortunately, the sober minds have congregated and stopped it there. This is preposterous, but once again, that’s how corporate media framing influenced public opinion, and that’s why we need an independent, a vibrant independent and free press to report these stories, to help analyze these things, and get people thinking more critically about the media they consume.

Eleanor Goldfield: Absolutely, Mickey, and again, I think,with regards to that, this also connects to a conversation that we had a while back about New York Times memos that said they weren’t allowed to use certain language. And I’ve mentioned the passive voice, but language and how we define things is also so important.

I mean, when people started calling it the genocide in Gaza, a lot of people got really uncomfortable. And my response was, you should be uncomfortable because genocide is horrific. No one should be like, okay, cool, genocide. It should make you uncomfortable. And when we read that word or when we hear it on a podcast or something like that, it should make us stop and take stock and say, okay, whoa, what is going on here?

And that’s exactly, of course, why they don’t want to use that word. Also because there’s this feeling in Zionist propaganda world that the Jews own the word genocide. So it doesn’t apply to, you know, the Rwandan genocide or the Armenian, it is specifically just for what’s known as the Shoah or the Holocaust of the Jews in World War II.

And so like at every turn, how things are phrased, what language, again, like going back to how Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting pointed out that, “when Hamas attacked on October 7th, this happened.” It’s like, no, no, no, no, no. Israel killed tens of thousands of people, including over a hundred journalists, end of sentence.

And it reminds me too, going back to the electoral politics conversation, it reminds me of a debate that I saw back in what, I guess it was like 2015 or 2016, where both Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders were askedif they were supporters of fracking. And Bernie Sanders’ answer was no.

And then Hillary Clinton gave like a five minute response that was just a bunch of equivocating, and at the end of it, you’re like, what are we even talking about anymore? I don’t even know what the topic, what was the question? And it was very reminiscent of how corporate media spins something so that you propose a question like, is a genocide happening in Gaza? And then by the end of it, we’re talking about something completely different, and you don’t know where we are or what the topic was. And it’s a very adept way of shifting focus and shifting blame, of course, and ensuring that people don’t get the straightforward, honest story from the front lines.

Mickey Huff: So well put. And I think so, so important for people to really ruminate on, especially the last couple sentences there. You know, I think that it is again possible that we have dialogue and conversation about these very difficult subjects, but I do think that when we broaden our media sources, and we’re able to see again, we’re back to the team red and blue thing. And even in that case, they’re kind of unilateral. I mean, they’re kind of like one mind on what’s happening with Israel, which is very problematic in that regard. Right? Democrats and Republicans are very pro Israel and the attacks in Gaza.

But I think that if we can get people who do maybe support this, maybe it’s a knee jerk support, maybe they have other reasons for identifying with that support.

I think it’s important that we’re able to get people to understand that just because something is telling a different story or a different perspective doesn’t make it fake news. It bothers me to see a lot of the neoliberals or Democrats using the fake news epithet that that they coined and that Trump weaponized against some of these other young people in particular on social media, because I think that we need to incorporate those narratives into and those perspectives into the bigger picture.

Because I don’t believe that everybody that’s cheering this on is doing so because they want to see some kind of genocide. I honestly think some of these people maybe do But there’s a host of other people I think that are caught in a misinformation maelstrom and by that I don’t just mean that they’re getting false information potentially, I just mean they’re only getting a part of the story which is more problematic because it leads people to match their confirmation bias and say well the New York Times has been right so far, and by the way, they did say in the 11th paragraph on the 116th day, you know, and so they kind of grasp at the straws to hold on to the blanket, like, ah, the New York Times.

And the New York Times does good work on occasion, of course, but it’s important to include all of these other narratives from independent media, and it’s very important to resist any effort to censor, shut down, or silence these platforms, these sources.

Because look, some of the tools that the Democrats are using to control discussion and debate. Imagine what somebody else might do who’s more authoritarian. Right? Just imagine if there might be somebody running for office right now that strangely could even be more authoritarian than the things we’re seeing now, Eleanor. I wonder what would happen.

Eleanor Goldfield: It’s hard to imagine because, you know, Obama creating the largest surveillance state the world’s ever seen and then Trump used it.

We have nothing to compare it to, Mickey. Yeah, I can’t imagine.

Mickey Huff: Yeah, and the latest attack has been on nonprofits, and Andy Lee Roth at Project Censored wrote a great piece for Truthout and Seth Stern, who was on the show last week, did a great piece at the Intercept.

So, you know, people need to wake up. The Congress is openly passing bills that are going to give the Secretary of the Treasury unilateral authority to revoke 501 C3 status from nonprofits by decree without due process. Let that sink in.

I know we’ve talked about this before, but I have to mention it again because Project Censored operates under a non-profit.

The Real News Network operates under a non profit. The Intercept operates under a non profit. Pacifica, we could go on and on and on here about the non profit status of so many independent media outlets. And this is the new tool. This would be the new weapon that allows of all people, the appointed secretary of the treasury, well, doesn’t that make sense though?

The purse, the money bags deciding what the nonprofits with no money get to say. But that’s what they’re doing next. They’re coming after the nonprofit news outlets next. And I don’t mean to sound alarmist. I’m telling people this because Congress already passed it.

They even tried to attach it as a rider on the FAA reauthorization bill, which has nothing to do with airplanes, right? It didn’t go through yet. We’re lucky. It didn’t make it onto the rider. But I want people to pay attention to what’s happening like this in Congress. Don’t just write it off cynically as like, it’s not for me or we can’t change it.

There are a lot of press freedom groups that have been screaming from the rooftops about these things, and we’ve gained a lot of traction to push back, right? To protect the non profit media space because it’s so important to have independent voices from across the spectrum, but it’s so important to have voices that are from the bottom up, not the top down.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, absolutely, Mickey. Very well put. And I guess I’ll just endthis segment with a question for folks to ruminate on, and that is: what is it that is so scary that must be censored and cannot be met in broad daylight and discussed and debated?

And I’m, I’m letting that question be open ended.

Mickey Huff: The question of the hour.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, yeah.

Mickey Huff: Indeed. Yeah. And I think a fantastic question to end on and perhaps we’ll even do a show in the future where we go into more detail or go deeper. Maybe we’ll even find some people with different views and perspectives that want to come on and actually have that kind of discussion, and debate where it doesn’t just turn into rhetorical tricks and name calling and insults and willful ignorance and willful misconstruing of facts and so forth.

I mean, the media can make a difference. The media can help propel meaningful discourse. It just depends if it’s for discourse sake in the public interest, or is it part of a more insidious, nefarious propaganda campaign to keep pretending we have a free press when we may not.

Eleanor Goldfield: Indeed.

Mickey Huff: Thanks so much, Eleanor. It’s been great talking with you in this segment of the program, and folks can learn more about the show at projectcensored.org. Eleanor, any other sites or places you’d like to tell people about that you could share with them so they can follow more of your work that you do outside of the program?

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, absolutely. All of my work is at artkillingapathy.com. Mickey, it’s always great to get on here and rap with you about the news of the hour that you won’t find other places. Thanks.

Mickey Huff: Thanks, Eleanor. And thanks to everybody for tuning in. We’ll see you next time.

If you enjoyed this segment, please consider becoming a supporter at Patreon.com/ProjectCensored

[/openrouter]

[openrouter]rewrite this title Uncensoring Congo & Digging Up Buried Leads in Gaza[/openrouter]

[openrouter]rewrite this content and keep HTML tags

519

/

In the first half of the show, journalist and activist Eugene Puryear joins Eleanor Goldfield to pull back the curtain of imposed corporate censorship on Congo. Eugene highlights the myriad forces of green imperialism scarring both land and people as the Congolese find themselves in a crowded crossfire of countries and militias vying for rare earth minerals. He shares insight on the growing grassroots movements for justice and liberation as well as why corporate media won’t and don’t cover Congo. Next, cohosts Mickey Huff and Eleanor Goldfield cover a new report that shows how cable and social media respectively shift how Americans view the ongoing genocide in Gaza. They also dig into a few ways in which legacy media bury the lead, lie through omission, and seek to obfuscate facts, not least of all when it comes to the targeted killings of frontline journalists in Gaza.

Video of the Interview with Eugene Puryear

Video of the Interview with Eleanor and Mickey

Below is a Rough Transcript of the Interview with Eugene Puryear

Please consider supporting our work at Patreon.com/ProjectCensored

Eleanor Goldfield: Thanks everyone for joining us, the Project Censored Radio Show. We’re very glad to welcome back to the show, Eugene Pier, who’s an American journalist, author, activist, politician, and host on breakthrough News.

He’s also the author of Shackled and Chained: Mass Incarceration in Capitalist America.

Eugene, thanks so much for joining us.

Eugene Puryear: Thank you so much for having me back. Great to be here.

Eleanor Goldfield: Absolutely. And Eugene, we had you back on the show in October to talk about what’s happening in Congo. And I definitely recommend that folks check that out, especially if you want more backstory on the issues that place the Congo as a battleground for immensely rich natural resources internally, via Rwanda and of course, so called Western powers like France and the US.

And one might call it an epicenter of green imperialism. So, Eugene, I want to start with April of this year when Congolese President Tshisekedi met with French President Macron to discuss quote unquote mineral mapping, which to me, just takes me back to the Berlin conference, like the mapping of, the cutting up of Africa. It feels very similar.

He was also seeking investments from French companies in both agriculture and the energy sector. So could you talk to us a little bit about the ownership, the current ownership of these mines? Who’s responsible for this child and slave labor, and what investment from imperialist powers would mean?

Eugene Puryear: Well, you know, it’s a great question. And I think pointing to the Berlin conferences is a critical reference point because what’s happening in the Congo really is a scramble for resources and a scramble for wealth on multiple different sides. And the trip of Tshisekedi to France is a big piece of that.

So, you know, in the current moment, it’s a bit of a mix in terms of the mines in terms of the different minerals, but most of the sort of critical minerals in Congo are mines that are Chinese companies usually partnered with Congolese companies. But then there’s also a niche for a lot of Swiss companies, quote unquote, but really it’s sort of Swiss domiciled American, primarily American and European countries. And then also you have UAE involved in a significant way, especially in the issue of gold.

And so one of the issues that has become a factor is that the Western countries have become very concerned that China has in their words, a quote unquote, stranglehold on critical minerals for the future, primarily cobalt, but also nickel, which are critical for the batteries, essentially, that are powering our everyday lives, but also copper, which is also mined in relationship with nickel and cobalt, which is a huge part of all the wires that we use. So really that the things that are powering our everyday life, if you will, are not only concentrated in Congo, but that most of them are then mediated through China, right? So it goes from Congo through some other African countries to China, and then they’re selling it to Apple and so on and so forth.

And so they, the Western countries want to cut out the Chinese middleman, so to speak, and they want their mining companies to be in a better position. And so France, following the United States, which has been doing quite a bit on this front, the United States is funding a new big mining project on the border of DRC and Zambia, which is actually where some of the worst abuses are taking place. Some of the ones that no one really knows about.

Some people think, and I think credibly so, there’s actually modern day slavery happening in a lot of these areas because they’re so remote. No one knows exactly what’s happening. And this is the area the United States is trying to penetrate its companies and its capital into.

Then they’re also along with France, and this is a part of this trip, building a railroad from a very mineral rich region of Congo through Angola to the Atlantic ocean to make it easier for Western countries to get access to these minerals.

So, Tshisekedi going to France, and Macron, of course, giving him a big red carpet treatment, as it were, was very much tied into the desire of French companies to get into the game where the U.S. companies are, where the Swiss companies are, where the Australian companies are. Australia, another big mining power, which is trying to essentially edge China out from this perspective.

So, to go back to the quick thing, and I’ll end here. In terms of the agreements and the terrible state of artisanal mining, which is, you know, people are being poisoned by mercury, there’s all these mine collapses, people are being hurt. There’s no education for kids. Clean water is being completely destroyed. And the amount of money they’re making is like, it’s so negligible it’s almost a joke to even talk about in terms of what they’re making year to year.

But to say all that, another big piece of Tshisekedi’s trip, and this has also been a big piece of what’s been talked about for the past year in Congo, is this idea of investing in small and medium sized enterprises. Now, of course, that sounds good to a lot of people, like small business, that’s good. But what that actually means is they’re expanding the realm of essentially subcontractors that are Congolese to cover for these various foreign companies.

So they’re going in and saying, you give more money to this person and that person who is tied to the presidential administration to be a subcontractor on your project. So it won’t really be Congolese control of Congolese minerals, but more of the wealth will be funneled to Congolese elites. And there are very few rich people in Congo percentage wise, but numerically, a very significant number of millionaires that are coming from this sector.

So they’re trying to expand that sector. And these people are really the people who I think are the most responsible in some ways for the conditions on the ground, because since all they care about is money and all they care about is getting their contracts, whether you’re coming from China, whether you’re coming from America, whether you’re coming from Europe, they’re just like, whatever y’all want to do to get this out of here, do whatever you need to do. As long as you pay us off.

And the Congolese military and some of these various armed groups often support these efforts to make sure that these things are happening, and capitalism being what capitalism is, the bottom line rules everything.

So if you can get the minerals out super cheaply, you’re going to do it. So I think it’s really a very important factor of what we saw in France is that the elites of Congo are trying to get more from France in order to basically sell their own country for parts and they’re trying to play the different countries off against each other to get the maximum amount of money for themselves while almost nothing trickles down to the average person who’s mining or living in these regions, doing agriculture or the like.

Eleanor Goldfield: Yeah, absolutely. And thank you for connecting those issues because it reminds us that we can’t talk about imperialism without capitalism and vice versa as well.

And I’m curious. I mean, we’re you’re talking about these mining regions. And of course, something that has pushed Congo to be discussed, not of course, on corporate media, which we’ll get to in a minute, but on alternative media sources is the extreme violence that’s happening there.

And as I understand it, and as you pointed out, this is part of this larger proxy war for these resources. And I also saw that earlier this year, the EU pledged 20 million euros to the Rwandan military to secure minerals for quote, clean tech and also a natural gas site for France. Just throw that in there as well.

At the same time, of course, uh, you have politicians like Macron talking about peace solutions for East Congo. And at this meeting between President Tshisekedi and Macron, a representative for the Congolese president cited France’s membership on the UN Security Council as, you know, a positive thing: oh, they’re going to propose resolutions for the DRC.